|

Location

Shılpıq is one of the most easily accessible monuments in Qaraqalpaqstan. It is situated on the right bank of the Amu Darya tuman,

some 44km south east of No'kis and just 6km downstream from the pontoon bridge at Qipchaq (or Kipchak). As you drive west on the A380 from Biruniy

towards No'kis, you first pass the Sultan Uvays Dag mountain range to your north. As the road descends from the mountains, about 88km from Biruniy,

it turns to the right revealing a panorama of the Amu Darya valley and the plain of the Qizil Qum. The distinct hat-shape of Shılpıq

stands out as the one prominent feature on the left hand side of the road.

The Shılpıq mount stands out like a beacon from the flood plain of the Amu Darya.

About 95km from Biruniy you pass a small works depot on the left hand side of the road. A number of dirt tracks fork off to the left, taking you to the

foot of the Shılpıq mount. Providing it is dry, the site is accessible with an ordinary car. Admission is unrestricted and free.

Shılpıq from the Amu Darya.

A nice way to view Shılpıq is to hire a small boat at the Qipchaq pontoon bridge and to sail down the Amu Darya for a few kilometres.

Shılpıq is only 600 metres from the right bank of the river.

Excavations

During the 19th century the monument of Shılpıq remained something of a mystery. At that time there was a medresseh adjacent to the

mount - it was sketched by the prolific artist Nikolay Nikolayevich Karazin when he visited the region in 1873:

Etching of a sketch of "Chilpik hill and medresseh" by N. N. Karazin.

When Ole Olufsen sailed past the monument in 1899 he noted that:

"North-east of Kiptjak on the eastern bank is a large medresse in a desolate place encircled by ditches near the river where the mullah-aspirants

study the Koran withdrawn from the noise of the world. Close by the medresse on a high bank is a small fortress, only consisting of a high circular

mud wall. This is the Kafir-Kala (Infidels' Castle) probably built by the Kalmuks who in the 12th century overran these regions under the command

of Jenghis Khan."

Shılpıq was first scientifically surveyed by Sergey Tolstov and members of his early Khorezm Archaeological Expedition in 1940.

Sergey Tolstov's survey of Shılpıq published in "Ancient Khorezm" in 1948.

Later investigations were conducted by Iu. P. Manilov in the late 1960s, although his work was not published in Tashkent until 1972.

Shılpıq

Although Shılpıq looks like a small fortress or qala it was most probably a royal dakhma, or tower of silence, where the

Zoroastrian priesthood exposed the corpses of Khorezm's ruling dynasty to the elements.

The sandy track leading to Shılpıq mount.

Shılpıq is the Qaraqalpaq spelling. It is often written as Chilpik, the transliteration from the Russian, and even Chilpyk. Some sources

even refer to it as Chilpik Kala, as though it were a fortress.

Since Uzbekistan achieved independence from Russia, Shılpıq has become an important national symbol for Qaraqalpaqstan, appearing

alongside the Amu Darya in its national emblem as a reminder of its rich historical past:

The emblem of Qaraqalpaqstan with the sun rising over Shılpıq.

It also appears in springtime banners and posters erected to celebrate the revived Zoroastrian new year celebration of Nawrıs.

A painted sign in No'kis declaring "Assalam Nawrıs", a peaceful Nawrıs holiday.

With the exception of Shılpıq , the right bank region of the Amu Darya to the north of the Sultan Uvays Dag is devoid of Bronze and Iron

Age archaeological sites. Because of the absence of any signs of human settlement, archaeologists have surmised that the whole region surrounding

Shılpıq may have had a long history as a sacred and restricted region.

Shılpıq clearly stands out today as a dramatic natural feature against the surrounding flat plain. Yet in the past it may have been even

more striking. There is evidence to suggest that there used to be a finger-like pinnacle protruding like a beacon from its summit. Sadly the

central stone at the top of the hill was destroyed during the Soviet era in order to install a geodetic survey trig point.

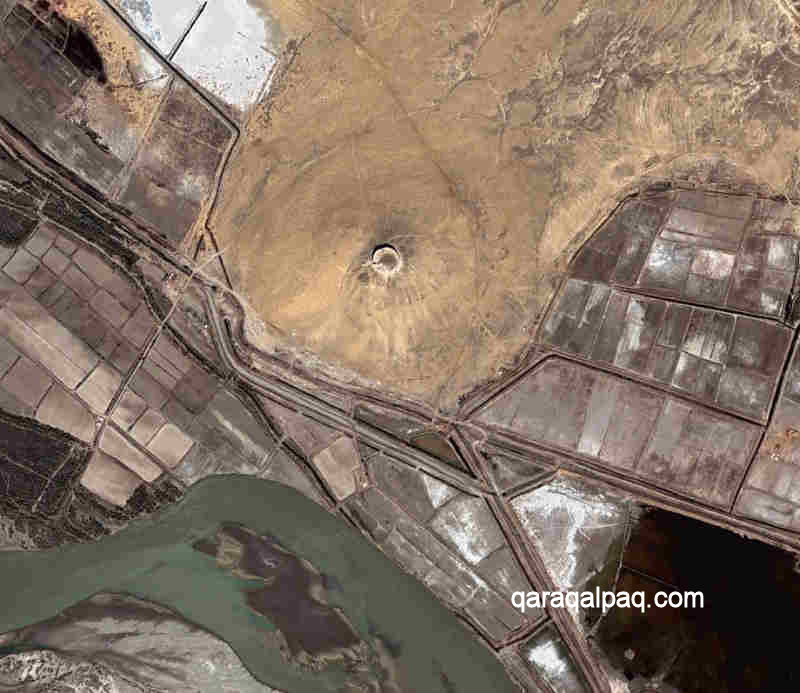

Aerial view of the Shılpıq mount. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Schematic plan of Shılpıq.

Image courtesy of Associate Professor Alison Betts, University of Sydney Central Asian Programme.

This unusual topography coupled with the presence of Bronze Age petroglyphs at nearby Qara Tube might indicate that the site provided a theatrical

setting for certain early religious ceremonies. Perhaps it was even a place of pilgrimage linked to the pre-Zoroastrian cults.

At some time from the end of the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD, a circular shaped enclosure was constructed on the top of the conical hill,

roughly 65 metres in diameter. The walls, which were tapered from a wide base, were built from pakhsa or compacted clay and reached a considerable

height. Today they still stand up to 15 metres high in places. There was an opening on the western side, linked to a 20 metre-long staircase that led

down to ground level. A tall tower was constructed at the bottom of the stairway, echoing the rock finger on the summit and providing a marker to the

entrance of the dakhma. This in turn was linked to a ramp leading down to the river.

|

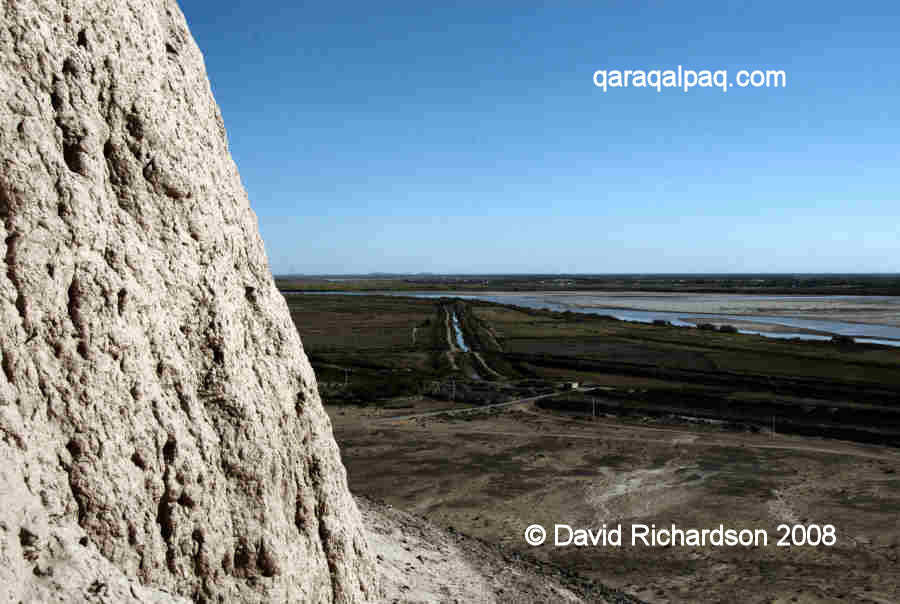

The remains of the pylon on the western side of Shılpıq facing the river.

The location of Shılpıq next to the Amu Darya. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Shılpıq seems to have been used up to the time of the Arab invasion in the early 7th century. There are signs of a phase of rebuilding

in the 7th to 8th centuries and later in the 9th to 10th centuries.

The official state religion of pre-Islamic Khorezm was Zoroastrianism, a religion that had developed from a much earlier cult of fire worship among

the steppe nomads. Zoroastrians believed that a human corpse was both physically and spiritually polluting, defiling the sacred elements of fire, water

and earth. The body of a deceased person was therefore placed in a raised location, known as a dakhma or "tower of silence", where it was

exposed to the birds and to the sun until the bones had been completely cleansed. The practise was briefly referred to by Herodotus in the 5th century

BC.

One of the dakhma situated just south of the town of Yazd in central Iran.

In Khorezm the skeletal remains were then placed in ceramic ossuary containers and buried so that they could not pollute the earth and vegetation.

Ossuary burial was a special feature of Khorezmian Zoroastrianism. It also occurred in other parts of Central Asia such as Sogdiana and the Semirechye

area, but it surprisingly never reached neighbouring Iran.

It was normal for the corpse to be left in the open for a period of a full year. It was thought that the west – the direction of the setting sun - was

connected to death and this may be why the staircase and its associated pylon were built on the western side.

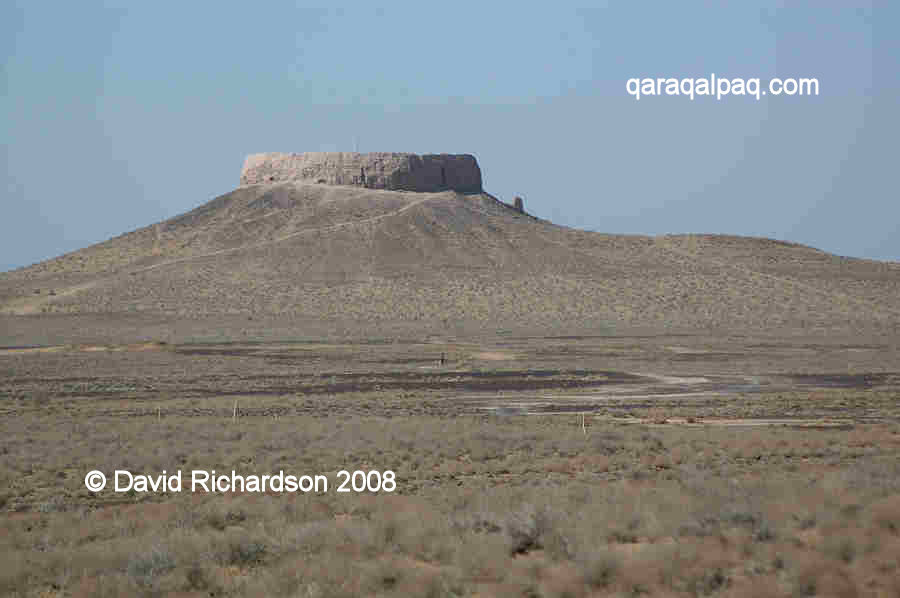

View of Shılpıq from the east.

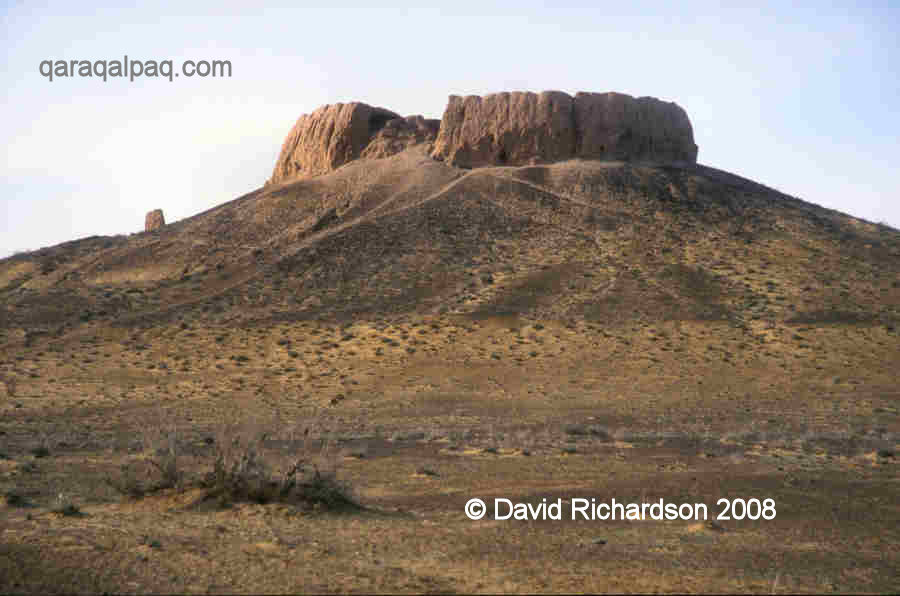

View of Shılpıq from the south.

Only a limited number of ossuarys were buried at Shılpıq itself. Many more have been found at burial sites in the nearby foothills of

the Sultan Uvays Dag, especially close to the once inhabited regions. Archaeologists have inferred that Shipiq may have therefore been reserved as a

dakhma for the ruling dynasty. After all, the royal summer residence – Topraq qala – had been constructed during the 1st or 2nd centuries AD

just 72km to the south-east. If so, the region would have been out of bounds to the ordinary populace, with access limited to the Zoroastrian priesthood.

The view of the river from the wall of the enclosure at Shılpıq.

What ritual ceremonies were conducted following the death of a Khorezmshah? Was the king brought down river by royal barge to the landing ramp at

Shılpıq? What was the scene as his body was ceremonially carried up the staircase for the final ritual - the exposure of the corpse

to the sun and the sky. Whatever occurred was concealed within the privacy of the enclosure crowning the top of the mount, well away from the prying

eyes of the masses.

Google Earth Coordinates

The following reference point (in degrees and digital minutes) will enable you to locate Shılpıq on Google Earth:

| | Google Earth Coordinates |

|---|

| Place | Latitude North | Longitude East |

|---|

| Shılpıq | 42º 15.840 | 60º 4.180 |

| | | |

Note that these are not GPS measurements taken on the ground.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|