The Qaraqalpaq Yurt

|

The Qaraqalpaq Yurt

|

|

ContentsOverviewSpecial Features of the Qaraqalpaq Yurt Types of Qaraqalpaq Yurt Materials Available for Yurt Construction Yurtmaking Crafts Pronunciation of Qaraqalpaq Terms References OverviewThe Qaraqalpaq yurt is unmistakable. Erected and fully decorated, it becomes a glorious expression of Qaraqalpaq folk art.

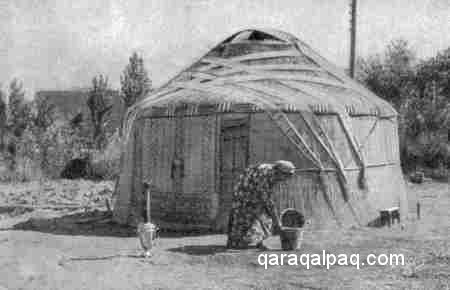

An idealistic image of the Qaraqalpaq yurt.

|

|

Yurts are normally associated with nomadic pastoral societies, so it is important that we remember

that the Qaraqalpaqs were not nomads. They were traditionally “semi-settled”, meaning that each

clan would have a wintering ground, qıslaw, and a summering ground, jazlaw, the two

usually not too far apart from each other.

In the winter the yurts would be erected inside a windbreak fence for protection, and another fenced

enclosure or qora would be built for the cattle. In the spring they would move their yurts

to the summering ground, close to the cultivated areas, allowing their herds to graze on the surrounding

pastureland and marshes. Working bullocks would be used to till the land. The awıls of individual

clans were often located close to a water channel to which the members of that clan had hereditary rights.

In the winter they relied on their agricultural by-products for forage: hay, wheat and millet straw,

ju'weri stems (sorghum), and cane. In the autumn the fodder would be harvested and

moved to the wintering ground by bullock cart or arba. In the marshy areas, especially

in the north of the delta, this fodder would be supplemented by harvesting the local rushes.

|

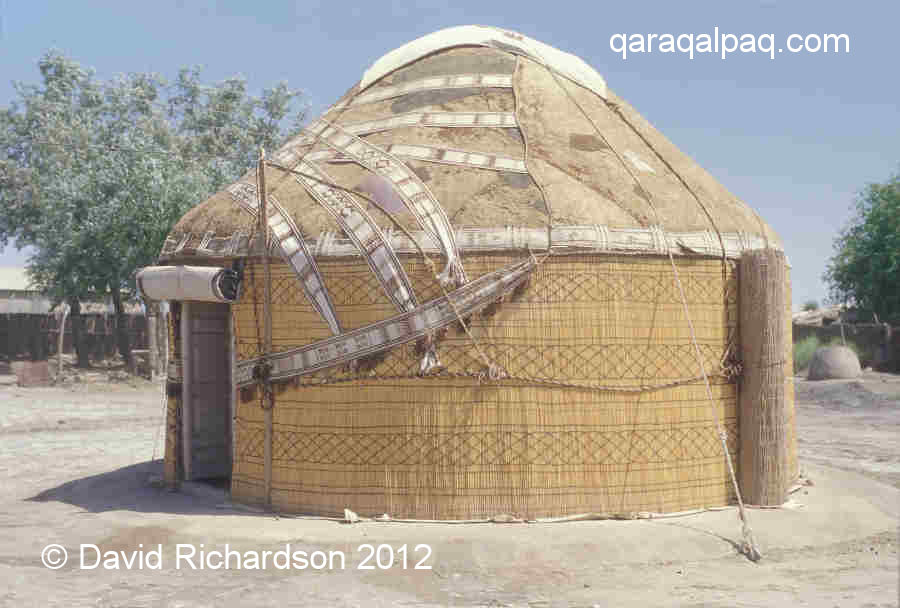

The Qaraqalpaq fisher-folk who lived in the northern part of the delta had a different lifestyle. Their awıls were often described as "cities of reeds" because their yurts had walls and roofs of reed, their farms had reed fences, and their cattle were kept in reed shelters. The men would depart on fishing expeditions, often making temporary camps on floating islands of vegetation while their nets were cast. In 1873 Major Herbert Wood sailed through the northern delta on the Russian gun-boat steamer "Samarkand" as a member of the Russian Imperial Geographical Society expedition to the Aral Delta. The sight of the local Qaraqalpaq fishermen was a shock:

"Poor and ill-clothed as these people are, each little gang of fishermen has a canopy or tent of cotton cloth, within which to pass their nights; for without such shelter, sleep, and perhaps, indeed, life, would be impossible, so innumerable are the mosquitoes and so painful are the bites of these insects in this locality."In addition to their seasonal migrations Qaraqalpaqs often had to move because of the changes to the river systems, which frequently flooded, forcing them to seek out new dry areas of land. In the same year of 1873 A. V. Kaulbars observed that:

"Approaching the Karakalpak village, located near the small estuary, supplied with water by the Amu only at high water, we saw bustle; cries were heard from all sides; property and nomad tents were rapidly loaded onto arbas, and everything which was prepared was moved away somewhere in a hurry. Assuming that our unexpected appearance was the reason for this flight, we accelerated our step and sent our leaders to quiet the population. It proved to be, however, that the reason for the bustle was the rapid increase in the level of water in the adjacent estuary, and before our eyes the place occupied by the village was flooded, so that the arbas which had arrived late were being loaded by people already standing in water."Although Kaulbars recorded that every Qaraqalpaq in the delta was involved in farming to various degrees, not every clan was the same. Some engaged in simple agriculture while others relied on more sophisticated irrigational farming. Herbert Wood noted that the riverbanks were lined with dense beds of tall rushes backed by low, scrubby, thorny jungle. But beyond, on the higher ground, were wide and open pastures occupied by Qaraqalpaq herds of cattle and occasional encampments with small agricultural plots. Closer to Qon'ırat there was more intensive irrigated agriculture, supplied with water by wheels powered by horses. Here the Qaraqalpaqs were growing wheat, barley, oats, and melons as well as lucerne for animal feed, and, on the wetter ground, rice.

|

However the yurts of the Khorezmian Uzbeks and the southern Kyrgyz also had a conical roof, the uwıqs

having a single bend about 45cm from the end, just like the Qaraqalpaq. Of course Kyrgyz yurts were never seen

in the Aral Delta, but Uzbek yurts were quite common in the 19th century, especially on the left bank of

the Amu Darya.

The main difference between the Qaraqalpaq and the Uzbek yurt lies in the kerege trellis wall: Uzbek qanats

were made from thicker and rounder poles and had much smaller lattice openings (ko'z). Zadykhina reported

that an Uzbek yurt could weigh three times as much as a Qaraqalpaq or Qazaq yurt, the reason being that the Uzbeks

were settled so their yurts were never moved. In the winter, even though the felts and shiy screens were

removed, the frames were often left in situ. Another obvious difference between Qaraqalpaq, Qazaq, and Uzbek yurts

is that the frames of the latter were never stained red.

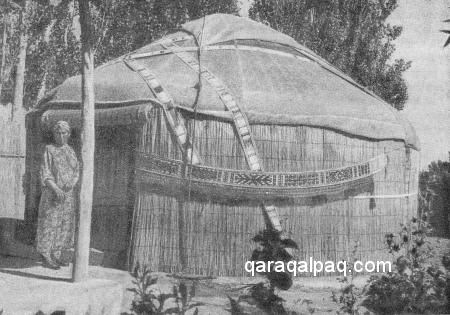

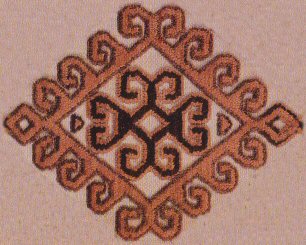

When properly decorated, the Qaraqalpaq yurt can be immediately identified from the white tent bands criss-crossing the roof,

the shiy screen walls, the jolly pink and brown janbaw suspended like a garland on either side of the door,

and the bold ram’s horn motifs on the weavings flanking each side of the door.

|

The one complicating feature is that within the Aral Delta some Qazaqs and Uzbeks purchased their tent bands from

the Qaraqalpaqs. Consequently some of the yurts in regions such as Qon'ırat that were owned by Aral Uzbeks still had the

appearance of a Qaraqalpaq yurt.

Types of Qaraqalpaq Yurt

The normal yurt is called a qara u'y, meaning black home or dwelling, so called because over time the covering

felts become darkened. This was especially so in the old days when every yurt had a hearth. Some well-to-do families

erected two yurts: one, the qara u'y, was used as the living quarters for the elderly relatives and children;

the other, the otaw (sometimes transliterated as otau or otav), was used for leisure and for

receiving guests.

Wealthier families would also erect an otaw at the time of a wedding, so that the bride and groom could spend

their first nights together in private. This would be specially decorated as part of the wedding celebrations, its

furnishings being an obligatory part of the bride’s dowry. However Anna Morazova noted that the distinction between

a qara u'y and an otaw was a fine one, since the decoration of some qara u'y was just as good

as that for a new otaw.

It is possible that the word otaw derives from otüy, the word used by the Noghay for a similar marriage tent.

Andrews quotes Bonch-Osmolovskiy, who noted that some writers refer to the Qazaq white tent as an ota-üy.

The term white tent refers, of course, to a new yurt as opposed to an old or blackened one.

|

We should note here that although the word yurt has now become completely established in the Western vocabulary as a label

for a portable trellis-walled dwelling, its use is not strictly correct. Today the yurt is actually the ground on which

the trellis-walled dwelling (the so-called yurt) sits – the Qaraqalpaqs call this the jurt. In the past the

Turkic word yurt referred to a territory, such as a camp site, an expanse of steppe pasturage over which an individual,

family or clan held grazing rights, or an estate from which an aristocratic tribal leader derived an income. The

misattribution comes from the Russians, who described a nomadic dwelling as either a yourta or else a

kibitka. The latter is also incorrect, being derived from the Turkic kebit, meaning booth.

Most Turkic tribes use the word for dwelling to describe a yurt, such as ev, öy, or üy.

For simplicity we will continue to use the word yurt, which is now a well-established and understood term for a portable,

felt-covered, trellis-walled dwelling in the West.

Materials Available for Yurt Construction

In the past the lower reaches of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya supported a unique and thriving natural environment.

Numerous winding channels, oxbows, and sweet-water lakes were separated by extensive marshes and swamps, many choked with

dense stands of reeds and rushes, some up to 8 metres high! In some areas the perennial reeds formed floating islands

of vegetation, called kupaki by the Qaraqalpaqs. The surrounding banks were covered with impenetrable tangles

of tugay forest, with shoreline communities giving way to reedbeds, then gallery forests, then fringe shrubs,

sedges, and finally desert, the latter providing patches of low-quality pastureland along its fringes. Endemic varieties

of poplar and willow dominated the forests, while tamarisk and elaeagnus filled the shrub thickets. This dense

vegetative cover provided habitats for a rich spectrum of wildlife: birds, waterfowl, large and small mammals, amphibians,

and, in the spring, huge quantities of mosquitoes.

|

People have lived in this region since antiquity, generally following a similar lifestyle centred on cattle-breeding and fishing.

This has led some to assume that there must have been a continuum of occupation within the deltas, the Qaraqalpaqs being

descendants of the original Apasiak marsh dwellers who entered the region over two and a half millennia ago.

The heterogenic nature of the Qaraqalpaqs and their genetic similarity to the Khorezmian Uzbeks proves that this cannot be so.

The explanation for this similarity in lifestyle is quite different – the special features of the delta environment determine

the domestic economy of the peoples who successfully inhabit it. For example the Kelteminar people, who arrived in the region

in the 4th millennium BC, built communal shelters made of poplar which they roofed with reeds. They were hunter-gatherers who

lived primarily by fishing and hunting game. Later pastoral inhabitants, such as the Tazabagyab, the Apasiaks, the Jety Asar,

the Pechenegs, and the Kerder were all cattle-breeders, who supplemented their diet through fishing, hunting, and simple farming.

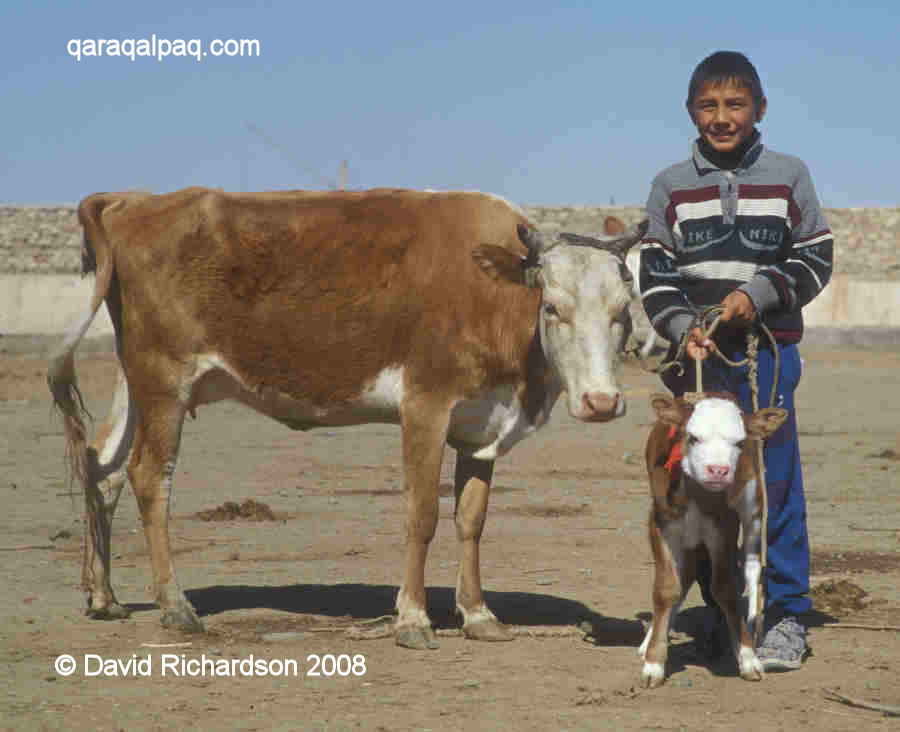

In the 19th century the Qaraqalpaq Qon'ırat, who lived in the northern part of the delta, were mainly cattle-breeders and fishermen,

while the lives of the more southern dwelling On To'rt Urıw principally revolved around irrigated agriculture. Some cattle were

raised in stalls using both agriculturally grown and natural fodders, while some were driven to summer pasturelands and were

only corralled in the winter.

|

Unlike the nomadic Turkmen and Qazaqs, the semi-settled Qaraqalpaqs did not specialize in raising sheep until well into the

20th century. Even then there were only two specialist sheep-raising kolxoz, both utilizing land on the fringes of

the delta. By contrast, the Turkmen long ago developed sheep farming into a refined art, breeding varieties specifically for the

quality of their wool.

|

Sheep and camels were not suited to the marshy, frequently flooded lands of the delta, while cattle and goats thrived, feeding on

the extensive reedbeds and tugay forest scrub. Of course sheep were bred in limited numbers in certain Qaraqalpaq

awıls – in 1873 the Russian writer A. V. Kaulbars observed Qaraqalpaqs keeping young lambs and kids inside the yurt for

protection and observed them seasonally migrating with "fine bulls, cows, calves, goats and sheep...". Herbert Wood saw Qaraqalpaqs

moving both cattle and sheep by boat later the same year.

|

However the overwhelming majority of sheep (and camels) were raised by the neighbouring Qazaqs and Turkmen on the drier low-quality

pastureland surrounding the delta. This was to be found on the fringes and in the hearts of the Qizil Qum, Qara Qum, and Ustyurt deserts.

Camels too were not common among the ordinary Qaraqalpaqs but were kept by the more wealthy bays, who of course were the most

likely to have the best quality weavings.

Wool was available to Qaraqalpaqs, therefore, but not as a major commodity unless, of course, it was purchased from the neighbouring nomads.

The main materials available for the construction of dwellings, the weaving of tent bands and the production of containers were as follows:

| - qamıs, or reeds, which grew in abundance close to the river channels and canals, |

| - jeken, or bulrush, used for making rope, aprons, and shıpta mats, |

| - shiy, a tall and thin but inflexible rush-like grass that once grew prolifically in the delta but has now died out as a result of soil salinization, |

| - kendır or wild hemp, |

| - aq tal (Salix oxica) and qara tal (Salix australior), both introduced species of willow, and aq terek (Populus alba pyramidalis), white poplar, |

| - qazan or goat hair, which had longer fibres than sheep or camel wool that were more resistant to sunlight degradation, |

| - paxta or cotton, which had been grown domestically in Khorezm long before the introduction of Soviet monoculture, |

| - leather, animal skins, and fur pelts, |

| - horn and bone from goats and cattle, |

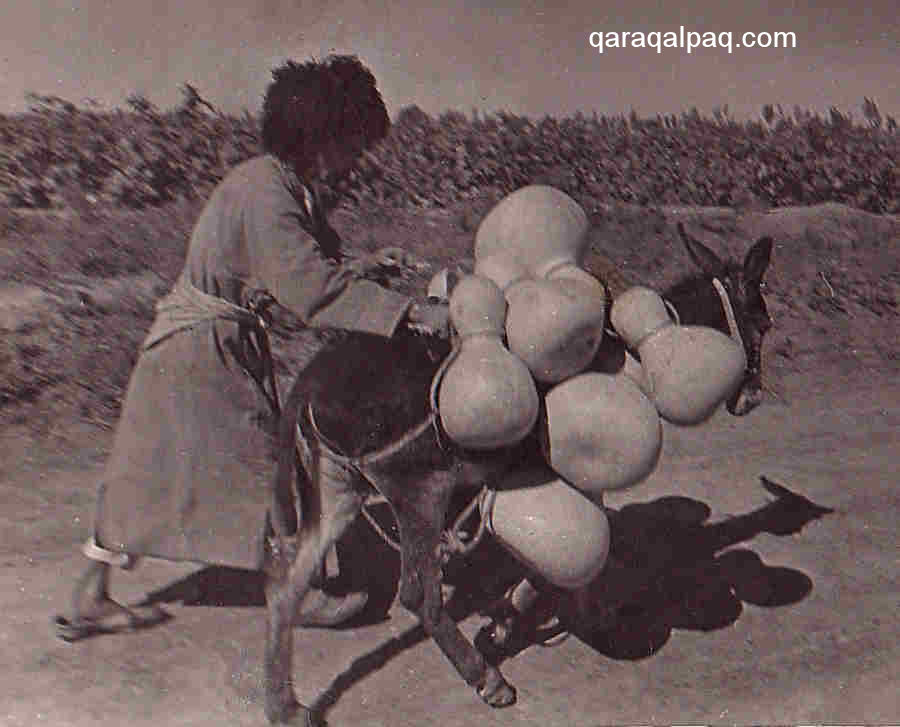

| - qabaq, or dried pumpkins and gourds, |

|

The Qaraqalpaq yurt and its contents were all constructed from these local materials. The components of the yurt

frame and the doors were made from local willow and poplar woods, tent bands were woven from either goat hair or

cotton, felts were purchased from local Qazaq nomads, and screens and outer doors were made from goat hair and

shiy, more latterly, qamıs. Inside the yurt, mats of reed or rushes were spread on the floor

and were covered with simple felt mats and quilted cotton ko'rpe. An alasha gilem woven from goat hair

or sheep’s wool might hang on the kerege to decorate the to'r and goat hair tassels might hang

from the roof. Grain might be stored in a hemp sack, while other provisions would be kept in leather, skin, or

cotton storage bags, or perhaps hollow gourds, all hung from the keregebas.

|

A wooden sandıq would hold the family valuables with a rectangular qarshın bag, made from goat’s hair

with a woollen pile front, for storing clothing on its top . Plates and cutlery were stored in a simple

or perhaps a decorated cotton kergi storage bag. If the family was well-to-do, a small rectangular

woollen-piled esikqas would decorate the space above the door. The husband's leather saddle and riding

tack was hung from the kerege in the male side of the yurt.

Yurtmaking Crafts

Various crafts were employed to fashion these raw materials into the yurt and its associated artefacts. The

manufacture of yurt frames required the specialist skills of workshops with yards to store the seasoning timber,

and ovens to heat-treat the wooden laths. The construction of door frames, sandıqs, and sabayaqs

required carpentry and carving skills. Both were the preserve of male craftsmen.

However the textile components of the yurt, including shiy screens, were all made by women in the home.

Until the 1920s it was the responsibility of every young girl to make her own dowry or baw shuw in time

for her future wedding. This process could begin when she was still a child and she would receive help from her mother

and any elder sisters or female relatives. In addition to costumes for herself and her mother-in-law, the dowry included

a full set of tent bands and decorations for the matrimonial yurt, including an aq basqur, an esikqas,

internal and external janbaws, a qarshın, and possibly a kergi tent bag.

In the case of wealthy families the parents of the fiancé would provide the frame of a new yurt, or otaw, for

the young married couple, which would be assembled and decorated with the bride’s tent bands at the time of the marriage

ceremony. Less wealthy parents might be forced to accept a yurt from the bride’s parents. In the case of a poor family's

wedding, the married couple might have had to live with the groom’s parents for many years before they could afford a yurt of their own.

Whatever the circumstances, the responsibility for producing the woven yurt components fell on the young future bride.

Weaving was an essential female skill and a good weaver was assured of a good husband. Fortunately all of the items required –

even the all-pile weavings - could be woven on the same crude and simple loom, the o'rmek, which is found throughout

Central Asia and as far as Iran and Afghanistan. It has a single heddle suspended from a tripod or four-legged trestle and

the two alternating sheds are formed by raising or lowering a shed stick. The girl would begin with the simplest weavings,

such as dizbe or qur, working her way up over the years to the most complex tent band of all, the aq basqur.

|

Of course talented craftswomen continued to weave after they were married, making items for their own families or for sale or

barter. For example it was reported that many Qazaqs and some Uzbeks purchased their tent bands and decorations from the

Qaraqalpaqs, just as the Qaraqalpaqs obtained the felt coverings for their yurts from the Qazaqs. There are also reports that

Qazaqs purchased Qaraqalpaq jez shiy screens. It was only later, during the Soviet era, when skills were being lost

that some craftswomen began to specialize in the production of shiy screens and tent bands for sale and markets developed

for the sale of second-hand items – for example, Shımbay Sunday bazaar became an important centre for buying and selling yurt

parts and tent bands.

Pronunciation of Qaraqalpaq Terms

To listen to a Qaraqalpaq pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

| aq basqur | kerege | qara u'y | sandıq |

| dizbe | kergi | qarshın | shan'araq |

| esikqas | ko'z | qıslaw | shiy |

| janbaw | o'rmek | qur | to'r |

| jazlaw | otaw | sabayaq | uwıq |

|

This site was last updated on 6 March 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2018. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |