|

Identity

Over the past decade the appellation Kazakl'i-yatkan has become the most commonly used name for this site in both the archaeological literature and

the popular media. Kazakl'i-yatkan is an English transliteration of Казаклы-яткан,

the simplified Russian form of its local Qaraqalpaq name - Қазақлы-яткан

in Cyrillic or Qazaqlı-yatqan in Latin. The literal meaning of the name is "Qazaqs are lying down". The term dates from the early 1930's

when the area was occupied by exhausted Qazaqs who had fled south from the chaos and starvation engulfing western Kazakhstan following Stalin's

enforced collectivization.

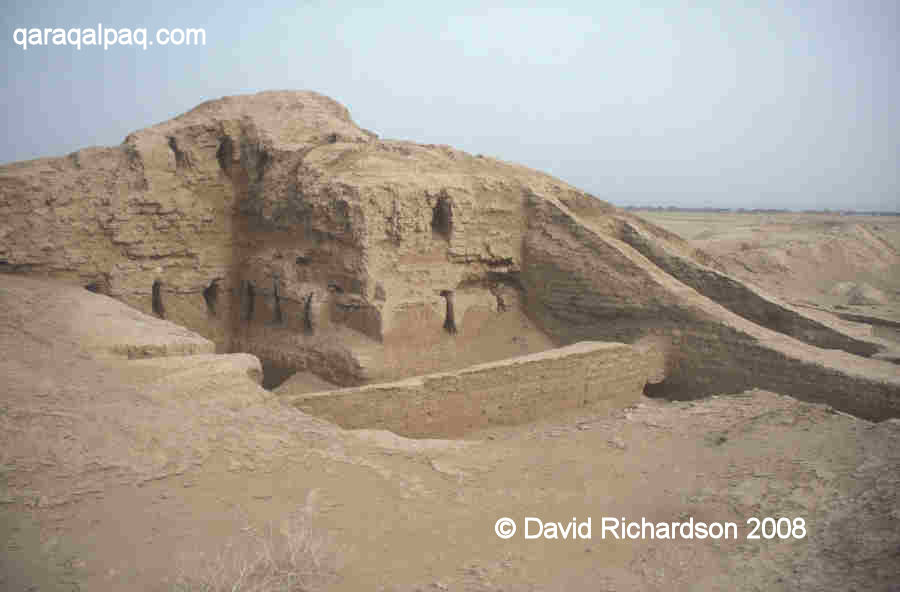

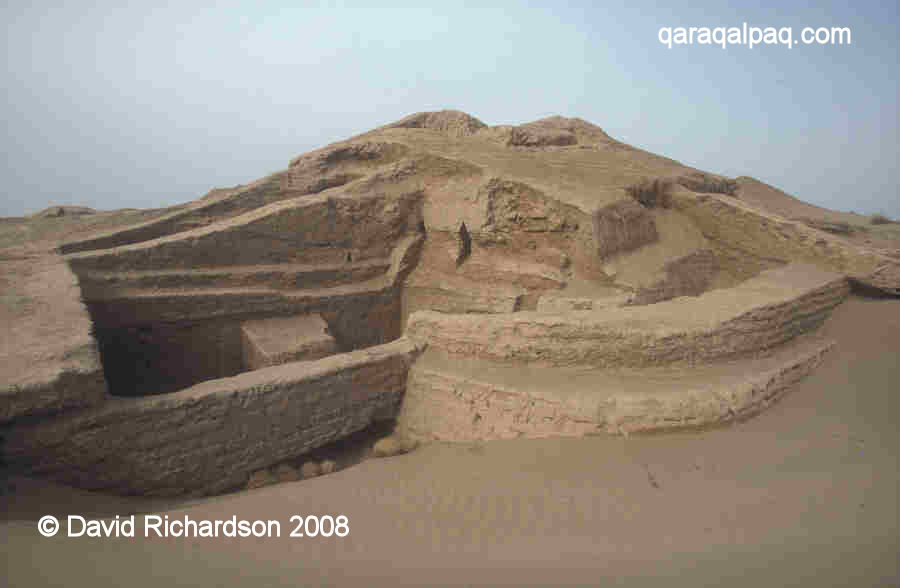

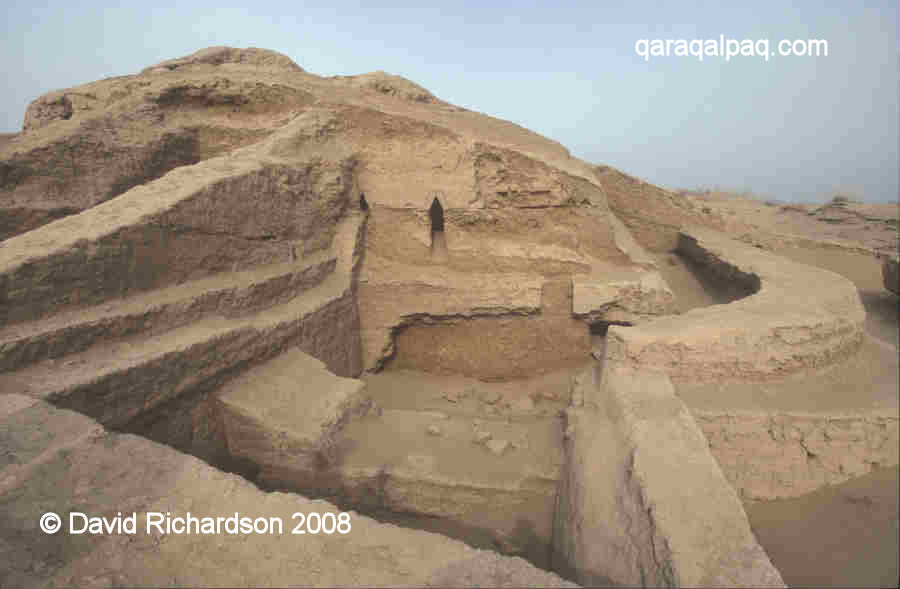

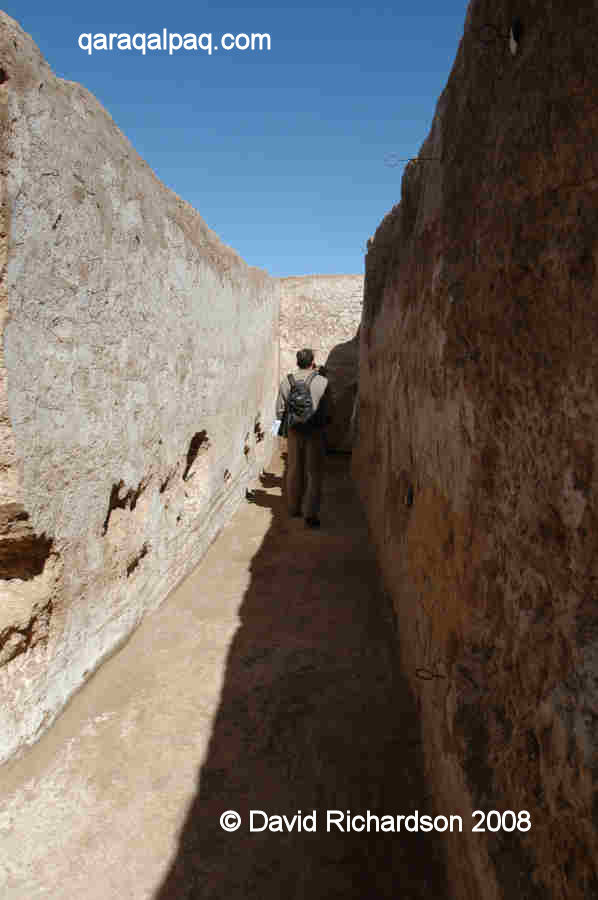

The corner tower and outer wall of the citadel of Kazakl'i-yatkan in 2003, following

their excavation by the Qaraqalpaq-Australian Archaeological Expedition in 1999 and 2000.

Prior to this time the site was known by the local Qaraqalpaqs as Ақша Хан Қала

or Axsha Xan Qala, transliterated to Akcha Khan Kala or Akhcha Khan Kala from the Russian. The name is derived from a legendary leader of the same name.

Location

Kazakl'i-yatkan is just over 15km north of Biruniy city centre and 13km south of the escarpment of the Sultan Uvays Dag.

It lies in the north-western part of what archaeologists now call the Tash-k'irman oasis, a former agricultural region that was once watered by a

northern arm of the Akcha Darya. This outlet of the Amu Darya seems to have finally ceased its natural flow in the early centuries of the 1st millennium.

All that remains today is an extensive region of sandy desert and lakes known as the Aq Qum Sands, which extends for about 30km in a north-easterly

direction starting from the south-east of Biruniy. The most northern part of this strip of desert is known as the Daganıoldı Sands, and

this is the location of Kazakl'i-yatkan (Axsha Xan Qala). The sands, which come from the ancient bed of the Akcha Darya, have not only concealed the

site but have preserved it for posterity. The largest lake in the region, which forms the northern boundary to the Aq Qum Sands, is still known as

Akcha Ko'l.

Although the site is still being actively investigated, visitors are welcome but are requested to contact the site caretaker on arrival. The main

annual excavation season is from September to early October. Beware that some of the excavations from previous seasons have been reburied to protect the

monument from erosion.

It takes just under two hours to reach the site from Khiva. First drive through Urgench and cross the Amu Darya pontoon bridge linking the viloyat

of Khorezm with Qaraqalpaqstan. From the north bank check-point drive north for 2km and then cross the To'rtku'l road. Continue north for a further

1.6km and turn left onto the main highway for just 0.3km before turning right and continuing for a further 0.2km to the crossroad.

Turn left. From this point the road immediately bends to the right taking you in a northerly direction. After 1.4km you cross the main road and after

10.8km you take a left turn. The road, which has houses on both sides, continues west for 2.9km before bending to the north. From now on measure your

distances from this bend. Some 3.4km beyond the bend the landscape on the left of the road turns into desert. At 5.8km from the bend there is a right

fork which after 300 metres leads to the entrance to the site of Kazakl'i-yatkan on the right hand side. There are two buildings on either side of the

entrance, the caretaker's house on the right and the archaeologists' dormitory on the left. After reporting to the caretaker you can walk south across

the desert to reach the partially buried site.

The road from Biruniy forms the western boundary of the Daganıoldı Sands.

The caretaker's bungalow lies to the north of the site. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Alternatively you can reach the site from No'kis. It is only 115km as the crow flies but it takes 136km or about two hours by road. Leave No'kis on the

A380 highway to Biruniy. After 93km from No'kis the road passes the turn to the Badai Tugai Reserve on the right and after 109km it bends to the right

and then heads south from the mountains towards Biruniy. Just after Kalenderkhana, some 6½km from the last bend and 116km from No'kis, take the

left turn. In less than 10km this side road reaches a t-junction. Turn right. After a further 9½km there is a small left turn, just as the

landscape turns to desert. The entrance to Kazakl'i-yatkan is just 300 metres on the left.

Excavations

The Tash-k'irman oasis was first discovered and investigated by a detachment of the Khorezm Archaeological Expedition led by Boris Vasilyevich Andrianov

in 1956. Following its identification, Kazakl'i-yatkan was surveyed the same year using aerial photography. Andrianov's main discovery at this time

was an sizeable ancient canal, some 17 metres wide from bank to bank, along with its associated irrigation network, agricultural settlements and field

systems. The canal was then thought to date from at least the 4th century BC and continued to be used up to the 8th century AD.

The first explorations of Kazakl'i-yatkan took place as part of a survey prompted by the planned construction of the new railway line to the east of

the Tash-k'irman oasis. Kazakl'i-yatkan was surveyed and superficially examined in both 1982 and 1985 by G'ayratdiyin Xojaniyazov and his colleagues

from the Department of Archaeology at the Qaraqalpaq Branch of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR in No'kis. The team also discovered another

archaeological site 6km to the south-east of Kazakl'i-yatkan, which they named Tash-k'irman tepe.

However the first serious archaeological excavations at Kazakl'i-yatkan did not begin until 1996.

In 1992 discussions had commenced about the possibility of future collaboration between Professor Vadim Yagodin and his archaeologists at the Institute

of History, Archaeology and Ethnography in No'kis and Dr Alison Betts (now Associate Professor) and her colleagues in the Department of Archaeology at

the University of Sydney. The outcome was the formation in 1995 of the Qaraqalpaq-Australian Archaeological Expedition, tasked with the ambitious

objective of continuing the earlier archaeological work of Professor Sergey Tolstov and his Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition.

Professor Yagodin had been intrigued by the possible existence of a so far undiscovered ancient capital city. The Persian postmaster Ibn Khordadbeg,

writing around 850, made a brief comment that the capital city of Khorezm had been moved to nearby Kath after an earlier city named Dargash or Darjash

had been flooded. Previous archaeologists such as Yuri Rapoport, who masterminded the excavation of Topraq qala, assumed that Dargash - if it had ever

existed - must have been close to the present Amu Darya. However flooding does not necessarily imply total destruction. One possible candidate for

the lost city was the 32-hectare site of Bazar Qala, 32km north-west of To'rtku'l. However the larger 47-hectare site of Kazakl'i-yatkan, coupled with

the nearby ruins of Tash-k'irman, looked more promising and had the added attraction that they both remained virtually undisturbed. Both were close to

a region that had been flooded by an ancient body of water known as the Istemes Lake, mentioned by some 10th century writers.

Some of the archaeologists' tools. Kazakl'i-yatkan in October 2007.

The first season of work at Kazakl'i-yatkan began in September 1995 and has continued annually ever since. The work was initially directed by Vadim

Yagodin and Sven Helms, with assistance from G'ayratdiyin Xojaniyazov and N. Yusopov. The first major excavations in 1996 involved cutting long trenches

across the walls of both the inner and the outer enclosures to deduce the history of their structure and design, as well as an investigation of a

centrally located monument in the upper enclosure. Between 1997 and 2000 work concentrated on the fortifications of the eastern wall of the upper

enclosure. A structure in the north-west corner of the upper enclosure, thought to be a palace or temple, was first explored in 2000 identifying

fragments of a stucco frieze decorated with gold leaf. When excavations in 2001 uncovered fragments of painted plaster, the absence of a conservator

forced work to a halt.

|

Aerial image showing excavations along the eastern wall of the upper citadel. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

From 2002 onwards work has concentrated on exploring the detailed layout of the temple-palace, resulting in the discovery and conservation of a large

number of polychrome wall murals. The highlight so far has been the discovery in 2006 of a series of portraits. It is not clear whether these represent

real personages such as members of the ruling dynasty or legendary or mythical characters. It is clear that the site was an important royal and/or

religious centre, which may well have been the capital city of an independent Khorezm and the residence of its ruling Khorezmshahs. Whether it was Ibn

Khordadbeg's city of Dargash is impossible to say with certainty.

Kazakl'i-yatkan

Kazakl'i-yatkan is located in the north-western part of the small island of sandy desert known as the Daganıoldı Sands, stretching 5km

from north to south and 2½km from east to west. The sands are surrounded by cultivated fields, although less so on the eastern side. These sands,

which are up to 15 metres deep in places, cover all but the excavated parts of the site up to the top of its outer walls. Consequently from a distance

the qala looks just like an elevated region of the desert.

The Daganıoldı Sands with Kazakl'i-yatkan on the horizon.

It is hard to believe that this was once a bustling metropolis. Below the sands are the remains of a large fortified city, dated to the 3rd century BC

but possibly constructed on an older, earlier site.

Aerial image of Kazakl'i-yatkan. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

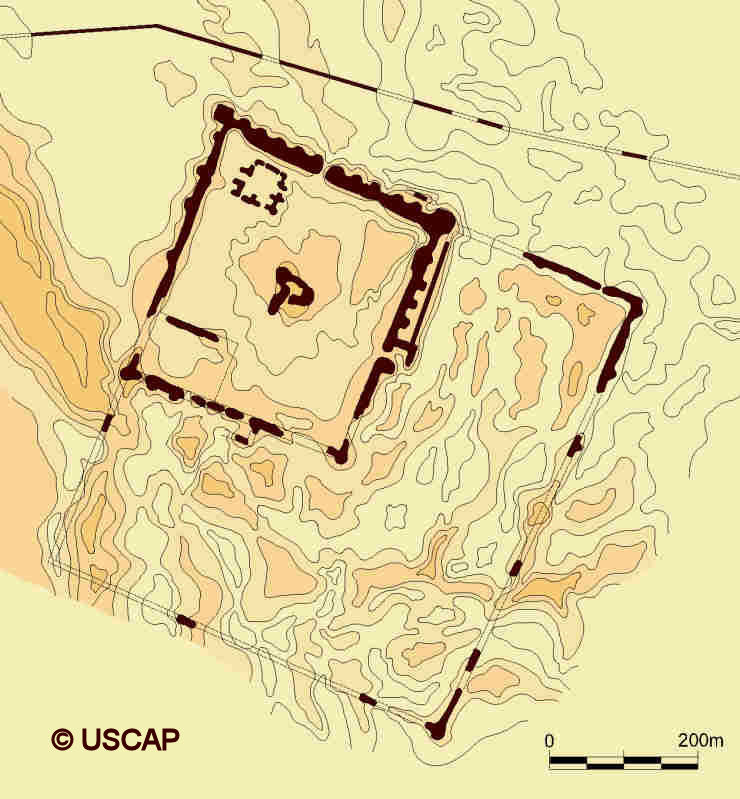

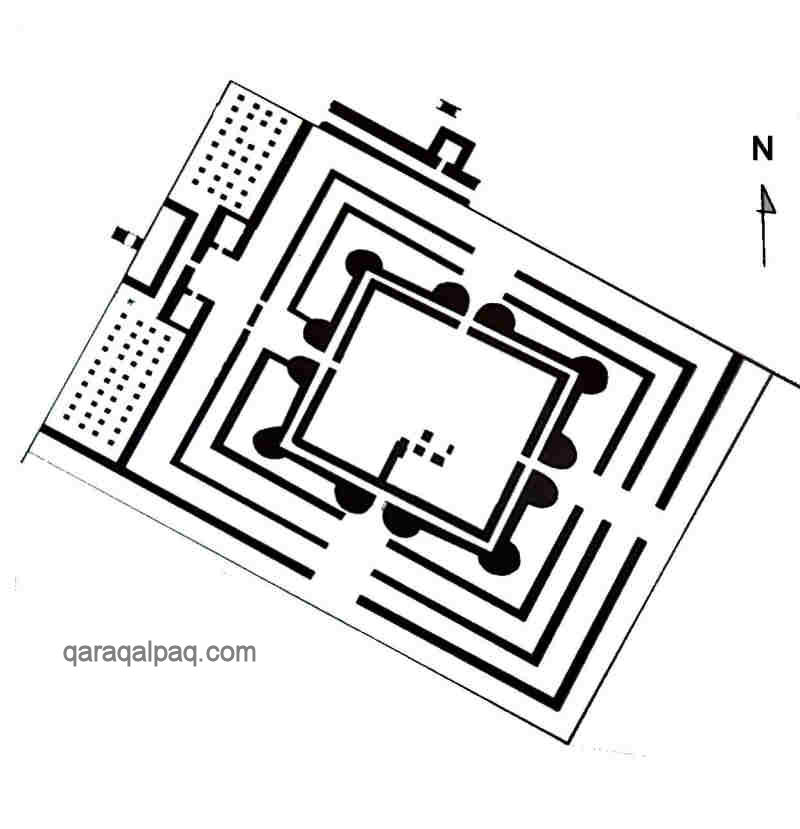

Plan of Kazakl'i-yatkan showing the upper and lower enclosures. Note the wall or causeway to the north of the site.

Image courtesy of Associate Professor Alison Betts, University of Sydney Central Asian Programme.

Kazakl'i-yatkan appears to have stood in the centre of an important agricultural region. In addition to the canal and irrigation system, the remains

of ancient fields, farmsteads, manors, pottery kilns and metal foundries have all been found in the surrounding area. Most of them seem to have been

active during the life of the fortified city.

The city of Kazakl'i-yatkan consists of two approximately square-shaped enclosures, both aligned so that their corners are roughly oriented towards the

four cardinal points – an upper level enclosure measuring about 380 by 340 metres, and a larger, lower level, outer enclosure measuring roughly 660 by

700 metres. The upper enclosure occupies the northern corner of the lower enclosure.

The Upper Citadel

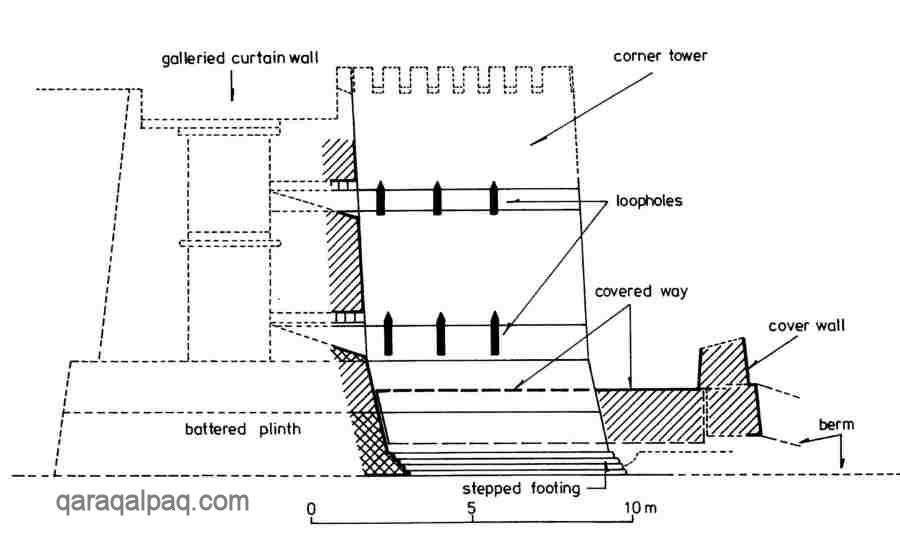

The upper citadel was defended by double walls, roughly 12 metres in height, built of unfired mud brick on a plinth, or socle, of compacted

clay or paqsa with a stepped outer base. It was reinforced with regularly spaced towers. The use of paqsa with the consistency

of concrete rather than mud brick was a new innovation, designed to foil an attack by battering ram.

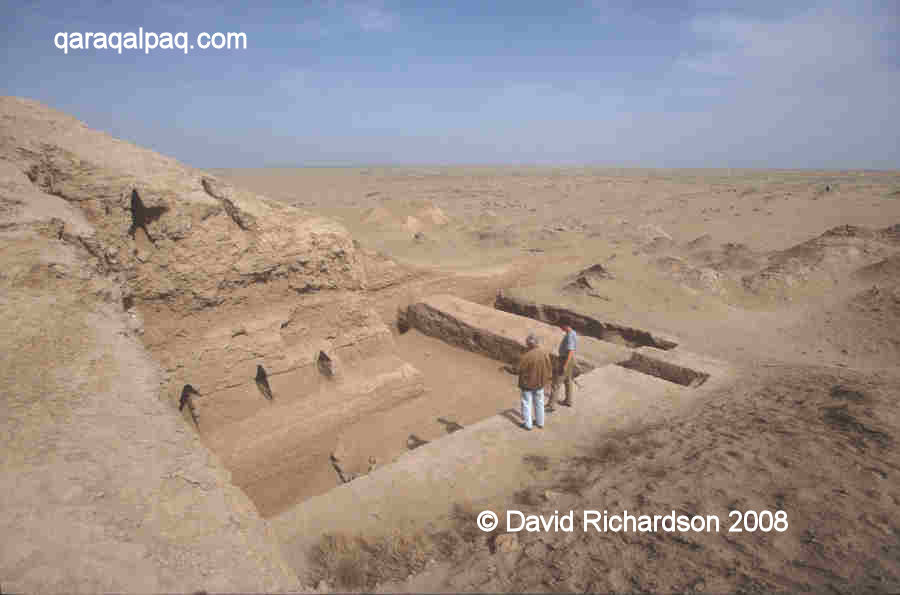

Looking towards the eastern facing wall and corner tower of the upper citadel.

The double walls of the lower enclosure can be seen on the right hand side.

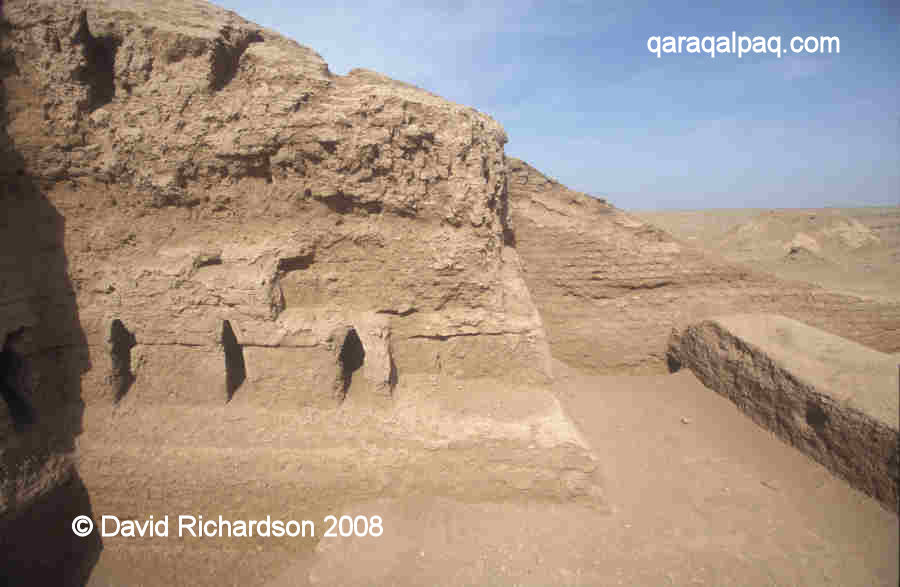

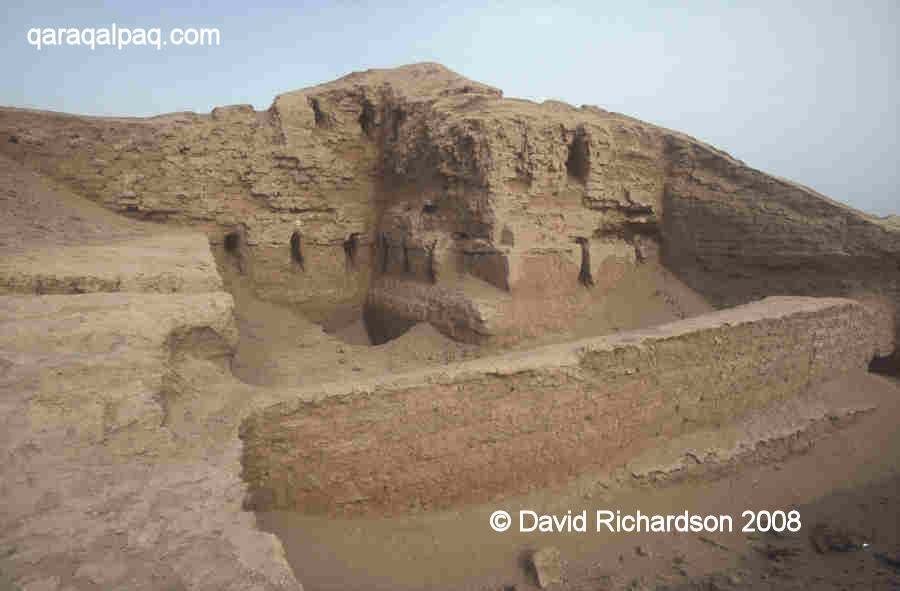

A slightly different perspective showing the two tiers of loopholes in the outer upper citadel wall.

Only the eastern facing wall has so far been investigated in detail and this had a centrally located entrance protected by a rectangular barbican

containing a single rectangular tower. Before gaining access to the citadel, visitors or attackers were first obliged to enter a small courtyard over

which the defenders had a complete field of fire.

A cross-sectional trench or sondage through the eastern barbican gate with the lower enclosure beyond.

The rectangular tower defending the labyrinth entrance is on the upper right.

The same trench looking towards the gateway in the eastern wall of the upper citadel.

There were five rectangular towers spaced along the curtain walls on each side of the entrance as well as two larger square-shaped towers at each corner.

One of the rectangular towers on the eastern wall of the upper citadel.

The space between the walls accommodated upper and lower archers' galleries and there were two tiers of closely spaced loopholes in the outer wall.

The lower tier of arrow-shaped loopholes in the eastern corner tower.

Viewed facing north. The inner face of the lower enclosure wall is on the right.

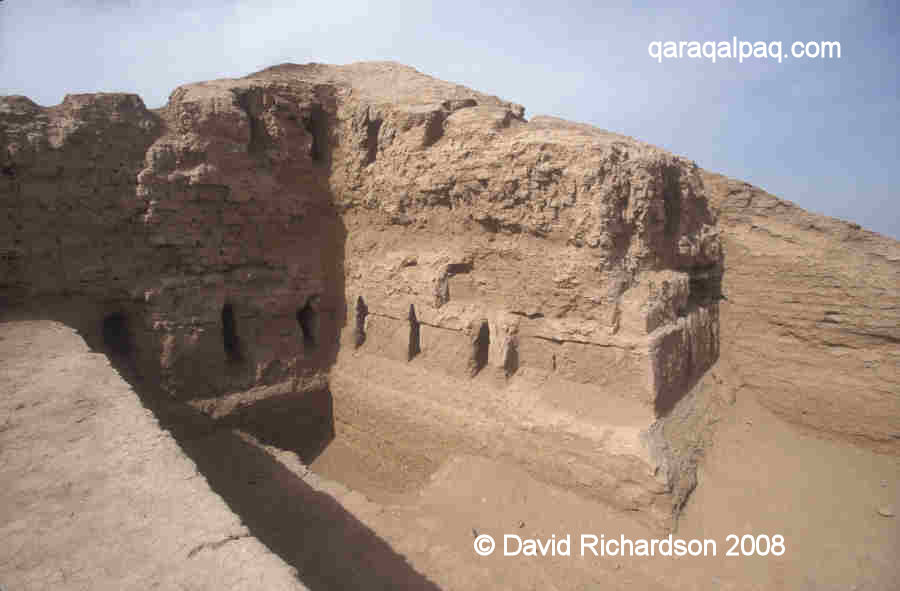

A different perspective of the eastern corner tower, showing part of the flanking wall of

the upper citadel and the second tier of loopholes.

The same view from the top of the eastern flanking wall with the sands beyond.

Professor Vadim Nikolayevich Yagodin in 2002, admiring some of his earlier work.

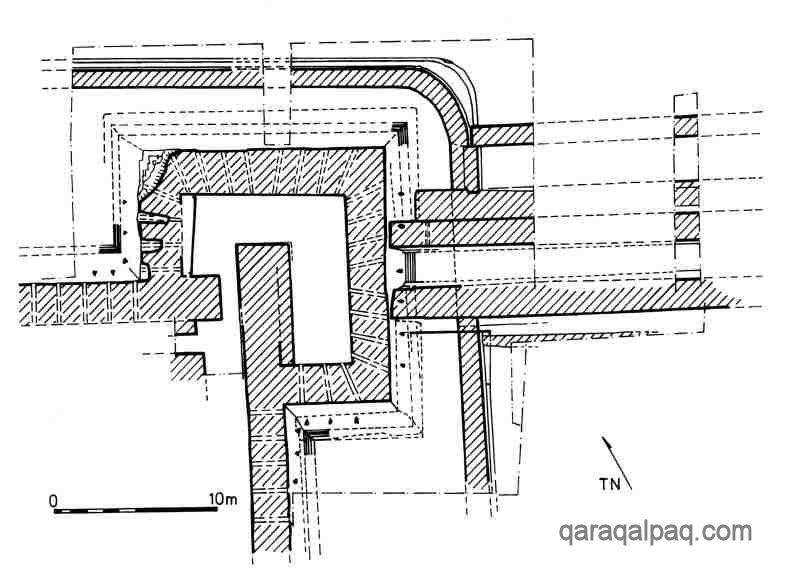

The loopholes in the corner towers were angled to provide a complete 270-degree field of fire.

Plan of the eastern corner tower showing the angled loopholes. On the right hand side is the double wall of the outer

enclosure, which was added at a later date. From Helms, Yagodin, Betts, Khozhaniyazov and Kidd, "Five Seasons of Excavations in the

Tash-k'irman Oasis of Ancient Chorasmia, 1996-2000. An Interim Report", Iran, Volume 39, pages 119 to 144, London, 2001.

It is likely that there was a third upper archers' gallery open to the sky and protected by battlements on the outer wall. There is evidence of a

second entrance and rectangular barbican in the centre of the south western wall.

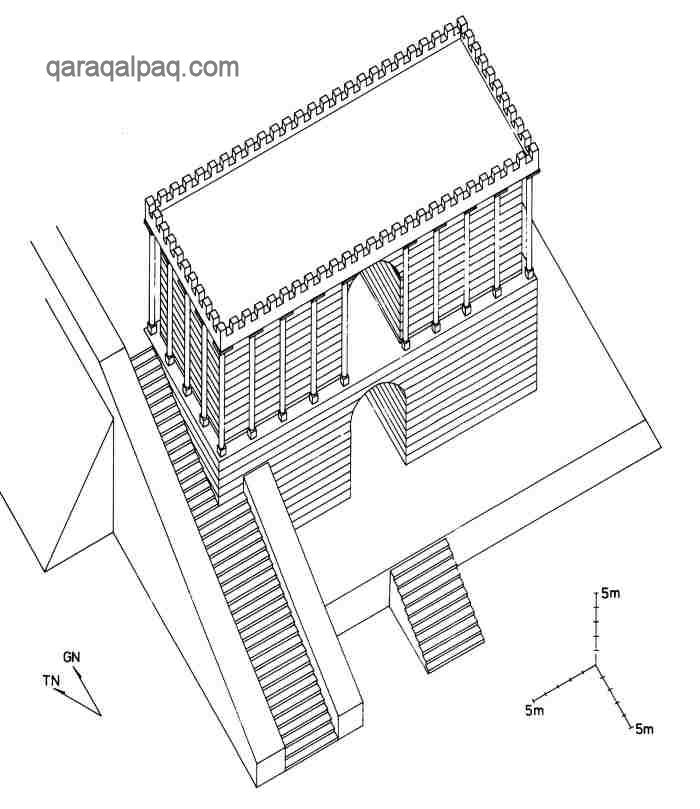

Illustration of the possible structure of the original tower and curtain wall.

From the interim report by Helms, Yagodin, Betts, Khozhaniyazov and Kidd, 2001.

The outer wall of the citadel was also defended by a low continuous barrier called a proteichisma, also made of solid paqsa,

positioned 3 or 4 metres in front of the foot of the wall. It had a raised mud brick paved walkway along its inner side and an outer double ditch

beyond. The proteichisma did not contain loopholes.

The proteichisma of the upper citadel curves around the eastern corner tower in the foreground on the right.

The proteichisma of the lower enclosure, which was added later, is in the foreground on the left.

A different perspective of the same location. When the lower proteichisma

was constructed, the upper proteichisma was modified to link in with it.

This outer defensive system has parallels with certain Hellenistic military fortifications, where such structures were designed to provide cover so

that archers could attack troops attempting to manoeuvre torsion artillery in range of the main curtain walls. The Khorezmians will have been fully

aware of such engines of war, especially after the invasion of Achaemenid Persia and the neighbouring province of Sogdia by Alexander the Great.

A section of the proteichisma guarding the upper citadel just inside the walls of the lower enclosure.

The upper citadel contains the remains of two unusual monumental buildings, one of which may have been a mausoleum and the other a religious temple and

perhaps palace, along with a walled open enclosure. There may well be the remains of other neighbouring structures so far unidentified. The preliminary

archaeological findings point towards the upper citadel being some kind of sacred high-status enclosure, possibly reserved for the ruling and religious

elite and their attendants.

The Mausoleum or Naus

The first monumental building is situated at the centre of the citadel, occupying a prominent position on a plinth at the centre of the upper city.

It is positioned so that it aligned with the central axes of the southern and eastern entrances. As such it may have been linked to the two gates by

roads.

An analysis of the foundations of the building and the fragments left from the collapse of its upper storeys suggests that it may have had the form

of a rectangular triumphal arch, perhaps up to 40 metres high. A pair of square-shaped side towers, two-storeys high, seem to have been connected by

two centrally positioned vaulted archways, one positioned directly above the other. The upper storey might have had an outer decoration of colonnades.

A ramp led up to the second level on the west side of the structure.

Reconstruction of the central mausoleum.

From the interim report by Helms, Yagodin, Betts, Khozhaniyazov and Kidd, 2001.

At some later date the building seems to have suffered a partial collapse. The western wall of the western tower was subsequently reinforced with an

angular buttress.

This was clearly a very important building that seems to have been in use throughout the life of the upper citadel. The excavation team have

speculated whether it might have been a mausoleum or Zoroastrian naus, a type of temple or ancestral shrine used for interring the bones of

the dead. If it was a royal mausoleum it may have been the resting place of one or more of the early kings of Khorezm.

The Temple-Palace

The second important building is situated in the northern corner of the citadel, next to the north-east and north-west facing perimeter walls.

Possible plan of the temple-palace. Note that only the western part of the building has so far been excavated.

From a presentation by Professor Alison Betts in Bostan, Qaraqalpaqstan in 2007.

Recent excavations have made it possible to suggest a preliminary plan. The building had a rectangular outer double wall separated by a corridor and

bulky rounded corner towers. There were also rounded bastions or towers on either side of the entrance on the north-western side and it is possible

that the other sides had similarly designed entrances. The whole building was surrounded by an outer rectangular gallery covered by a ceiling. This

in turn was surrounded by a street running around its outer perimeter. Facing the north-western entrance on the opposite side of the street was

probably a hyperstyle hall, with its ceiling supported by a forest of columns standing on carved stone bases. The design has parallels with the grand

hall in the Apadana at Persepolis or the Juma Mosque in Khiva.

Two views of the excavated western end of the temple-palace.

The presence of three fire hearths within the building indicates that it was, at least in part, used as a Zoroastrian religious centre. The discovery

of numerous polychrome paintings on the walls of the corridor running between the double walls on either side of the north-western entrance coupled

with finds of stucco decorated with gold leaf shows that it also had a very high status. The main images discovered to date consist of a procession of

horses, probably with riders, and a sequence of portraits showing women wearing elaborate costume, jewellery and headdresses. Research continues in

an attempt to discover whether these were members of the royal dynasty or religious, legendary or mythical characters. The conclusions could be

important in ascertaining the role of the building.

The northern section of the western corridor where the paintings of the female portraits were found.

The architectural design of this building is quite unusual for Khorezm, being closer to that of the much earlier Bronze Age Oxus Civilization temples

found in neighbouring Margiana (such as Gonur South, Togolok-1 and Togolok-21 north of Merv) and Bactria (such as Tillya-tepe south of the Amu Darya

in northern Afghanistan).

The Temenos

One final structure identified within the upper citadel is an open rectangular area measuring about 90 by 120 metres, located in the western corner,

just to the left of the southern entrance. It is bounded on two sides by the outer walls of the citadel and on the other two sides by solid

paqsa walls. It has been suggested that it might be a temenos, a sanctuary or sacred space reserved for the political or religious

aristocracy.

The Lower City

Our knowledge of the lower enclosure is more limited since the majority of it still remains unexplored. The main excavations to date have been limited

to the far eastern corner and to sectional trenches cut across the south-western and the north-western perimeter walls.

They show that the lower enclosure was also heavily fortified with galleried curtain walls, loopholes and an outer proteichisma. The remains of

domestic buildings were identified along the inside face of the curtain wall at the eastern corner, suggesting that this may have been the residential

and commercial area of the city.

The Defensive Wall or Causeway

Just over 100 metres from the north-east flank of the city wall is a further man-made feature – a field wall of causeway that has been traced for several

kilometres eastward. It is not clear whether this was a defensive wall designed to intercept nomadic cavalry or a processional way linking the site to

the Zoroastrian temple at Tash-k'irman tepe, 6km away.

The Wall Paintings

In 2006 wall paintings were discovered within the western corridor of the temple-palace. Remnants of paintings were also found outside the corridor,

one even being located on the inner city wall. It seems that the walls were originally painted at three levels, but unfortunately the lower levels

have been damaged by damp, salt and in some places algae. Some damaged paintings had detached themselves from the walls and were recovered from the

floor of the corridor. Up to a hundred of these images have now been removed and taken to the Academy of Sciences in No'kis for conservation. So far

just a couple have been placed on public display at the Qaraqalpaq State Museum of Art named after Savitsky.

Of the many images recovered, two sets stand out for attention. The first was recovered from the southern section of the western corridor. It consists

of a procession of five horses, with red horses at each end, a blue horse in the middle and black horses in between. There is the trace of a saddle

on one of the horses and the outlines of costumed human figures between the horses.

The head and headdress of a woman recovered from the temple-palace, possibly 3rd or 2nd century BC.

Image courtesy of the Qaraqalpaq-Australian Archaeological Expedition and the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

The most stunning images come from the northern section of the same corridor. They are a sequence of bold portraits of female figures with short black

hair, their faces dramatically made up with red lipstick, black eye make-up and red coloured ears. They wear white, or red and white headdresses, some

laced at the back with a ribbon and some decorated with what appears to be a bird or a crouching animal facing forward on the top. Some of the figures

wear torque-like necklaces with zoomorphic figures such as lizard or snake heads at the terminal ends. In some of the portraits it is even possible to

detect the signs of simple plain coloured or striped clothing.

Two more female portraits from the same western corridor.

Images courtesy of the Qaraqalpaq-Australian Archaeological Expedition and the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

The obvious question is who do these portraits represent? They are clearly not Khorezmshahs, so they could either be important living relatives or

ancestors of the ruling dynasty or perhaps more likely goddesses from the local religious pantheon. We know that some of the paintings from the temple

are mythical – one fragment depicts a creature with a horn and an eye. However even goddesses may have been depicted in contemporary Khorezmian costume.

Dr Fiona Kidd, a research fellow at the University of Sydney, is currently attempting to find some answers to these questions.

The History of Kazak'li-yatkan

Kazakl'i-yatkan is one of the few Khorezmian sites to have been dated absolutely using radiocarbon 14. Although the estimated phasing of the sites

development has not been fully finalized, the preliminary results provide a picture of how the site may have developed.

Kazakl'i-yatkan was anticipated to have been built in the 4th century BC, the era during which many other fortified sites in Khorezm were thought to

have been constructed. Its age turns out to be younger than expected. The upper town was the first part of the city to have been built - in the middle

of the 3rd century BC.

However the agricultural oasis in which it was situated is probably older. The canal that watered the region has its lowest layers dating from the 5th

century BC and it is possible that it is even earlier still. It is also feasible that the citadel was built to defend an earlier royal or high-status

burial site, although evidence is still needed to support such an idea. Finds of Archaic pottery provide at least some support for a period of earlier

occupation.

The mausoleum and the temple were first founded at the end of the 3rd or at the beginning of the 2nd century BC. They were followed by the addition of

the proteichisma and the construction of the outer walls around the lower town. Clearly the installation of outer defences must have been a

response to a perceived threat of attack by an enemy possessing artillery and other types of siege-breaking equipment.

The threat seems to have been real. In the middle of the 1st century BC the whole city seems to have experienced a major calamity, possibly the

aftermath of a successful siege. The roof beams in the archers' galleries were destroyed by fire and the outer wall of the upper citadel shows signs of

heavy battering in the vicinity of the eastern corner tower and the flanking wall just to its south. A stone ballista ball was also discovered close to

the same corner tower, sadly in an unstratified context making the dating of its delivery impossible.

After the siege the citadel was quickly repaired. The interior lower level of the eastern corner tower was filled with courses of mud brick. Later the

same corner tower along with the rectangular tower on the eastern wall (and one presumes many other towers) were clad with mud brick and paqsa,

concealing the lower tier of loopholes. Shortly afterwards the citadel seems to have fallen into disuse.

At some time during the 1st or 2nd century AD, there was a further phase of reconstruction and occupation. The lower gallery within the eastern wall

of the citadel was blocked up and paved over with mud bricks at the second storey level. Both this and the earlier repairs seem to reflect a clear

defensive response to the earlier siege. The remains of ash in the fire temple located within the temple-palace also date from this later period of

occupation.

During the 2nd century AD the citadel was finally abandoned. By now work must have been well underway, if not completed, at the two royal and religious

summer palaces at Topraq qala, just 14km to the north east of Kazakl'i-yatkan. We have no explanation of why the city was deserted other than Ibn

Khordadabeg's much later reference to flooding. Today the ground level of the city is close to the local water table and we know that the temple-palace

has certainly experienced flooding in the past (causing damage to some of its wall paintings – see later). Of course this might not have been a permanent

state of affairs - we must remember that flooding was a regular seasonal event in ancient Khorezm, very much dependant of the whims of the Amu Darya.

So far we cannot date any single flooding event to the 2nd century AD or indeed to any other specific period.

During the final phase of occupation, from the 3rd to the 9th century, the site seems to have been exploited by squatters.

The Mysterious Siege

The indication that the citadel may have been subjected to a devastating siege in the middle of the 1st century BC has created a puzzle that so far

remains unsolved.

Interestingly a significant number of other early Khorezmian fortresses show signs that they too may have been subjected to siege or destroyed by fire,

such as Gyaur Qala at Mizdahkan and Qoy Qırılg'an qala. Archaeologists from No'kis have previously dated many of these events to the

2nd century BC and have suggested that they may have been the result of long term siege by nomads. The 2nd century BC was a period of great upheaval

in the nomadic world, referred to by some Russian scholars as one of the "Great Migrations of Peoples". The Sarmatians had been migrating from the

southern Urals towards the Black Sea and one confederation, the Yueh-chih, migrated from as far away as the Gansu plateau of China and western Mongolia

to take control of neighbouring Sogdia and Bactria, displacing many other nomadic groups in their wake. Of course at this particular time these nomads

had no access to machines of war. All they had was the ability to bring a citadel to its knees by prolonged siege.

Today there is some concern over the previously accepted chronology of early Khorezmian history and therefore the dating of such siege events, if indeed

they truly happened. One of the outcomes of the work at Kazakl'i-yatkan has been to raise questions about the accuracy of dating methods based primarily

on the periodization of ceramics. Absolute dating seems to indicate that events occurred somewhat later than previously estimated. Perhaps other regions

of Khorezm may have been invaded in the 1st rather than the 2nd century BC?

In the 1st century BC there were only four regional powers with sufficient muscle to seriously challenge Khorezm's well-organized defences:

- The Kingdom of Parthia to the south, which was at that time engaged in a protracted war on its western front with Rome,

- the newly established and loosely knit Yueh-chih confederacy in Bactria, further up the Amu Darya, still a century away from emerging as a unified

Kushan power under Kajula Kadphises,

- the powerful K'ang-chü confederation of Saka-like nomads located around the middle Syr Darya and the lower Zeravshan, some tribes of which may

have acknowledged the authority of the Yueh-chih in the south, and

- the Sarmatian confederation of nomadic tribes, whose territories extended across the Pontic steppes on the north side of the Black Sea.

Although the Romans extensively utilized siege engines in their invasions of Parthia (disastrously so in the case of Mark Anthony), the Parthians never

responded by developing siege warfare machines of their own. Their military strength lay in their mounted archers and cavalry, just like the nomadic

K'ang-chü and Sarmatians.

Perhaps one should consider the possibility of whether the Yueh-chih gained access to Greek military technology following their conquest of the Seleucid

state of Bactria and whether they used it against their downstream neighbour. We know that the earlier Seleucids retained such a capability – hundreds

of ballista stone balls have been recovered from the Tower of David as a result of the Seleucid siege of Hasmonian Jerusalem in 134 BC. However

archaeological evidence from Aï Khanoum (Alexandria on Oxus) suggests that Bactria had already been overrun by Saka nomads a decade or more before the

arrival of the Yueh-chih. Its military engineers (if ever it had any) must have been long gone before their arrival. Unfortunately our knowledge of

Kushan history is at best poor and almost nonexistent regarding the early years. There is no record that they ever used siege technology in their

later conquests in the east.

We do know that the K'ang-chü extended their power westwards beyond the Syr Darya in the 1st century BC, subjugating the state of Yen-ts'ai –

literally "vast steppe", the steppes of the Sarmatian Aorsi tribe lying beyond the northern Aral Sea in the region of the lower Volga, progressively

being occupied by the Alans at that time. They also subjugated the country of Yen to the north of Yen-ts'ai. Yet there is no evidence that they ever

extended their authority into the southern Aral region and Khorezm.

At this time the majority of the Sarmatian tribes roamed well to the west of Khorezm, occupying the steppes to the north of the Black Sea. Indeed from

the mid 4th to the mid 1st century BC they moved further and further to the west towards the Danube, pushing the endemic Scythians into the Crimean

peninsula. During the 1st century BC the powerful Alans emerged as the dominant Sarmatian tribe in the eastern region between the Don and the Volga.

Archaeological evidence from nomadic burial sites on the eastern edge of the Ustyurt plateau to the north of Khorezm suggests that the Massagetae

deserted the Aral region during the 2nd century BC. It is not until the 2nd century AD that a new influx of nomads appears, with burial sites resembling

those found in the southern Urals and dating from the very same era. It has therefore been assumed that these may have been an offshoot of an eastern

branch of the Sarmatians such as the Alans.

We come to the frustrating conclusion that, at this point in time, there is no archaeological or historical evidence pointing towards any hostile state

or nomadic confederation with both the motivation and the resources required to overwhelm the capital city of Khorezm in the 1st century BC, let alone

one with access to Hellenistic siege technology. We have to wait until the emergence of Sasanian Iran in the early 3rd century AD before we see a

neighbouring power equipped with siege engines, an outcome of the long-running war between Parthia and Rome. Although historical references point to

several Sasanian raids on Khorezm in the middle of the 3rd century, this is 400 years later than the apparent great siege of Kazakhl'i-yatkan.

We are left with a conundrum that illustrates how little we still know about important stages in Khorezmian or indeed Central Asian history.

Google Earth Coordinates

The following reference point (in degrees and digital minutes) will enable you to locate Kazakl'i-yatkan on Google Earth:

| | Google Earth Coordinates |

|---|

| Place | Latitude North | Longitude East |

|---|

| Kazakl'i-yatkan | 41º 49.720 | 60º 43.050 |

| | | |

Note that these are not GPS measurements taken on the ground.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|