Qaraqalpaqstan Tour Guide

|

Qaraqalpaqstan Tour Guide

|

|

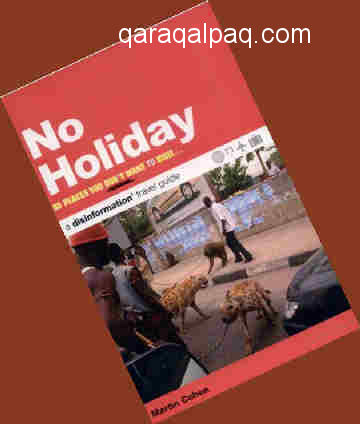

Visit Qaraqalpaqstan!Tired of holidaying alongside millions of other tourists? Sick of the thought of yet another predictable package tour? Feeling wild and adventurous? Then Qaraqalpaqstan is the place for you!Just think of the excitement of visiting a country that most people have never even heard of? One that is even listed in that wonderfully exotic travel guide "No Holiday: 80 Places You Don't Want to Visit". In Qaraqalpaqstan you can see the remains of one of the least-known lost civilizations of the ancient world. You can spend time exploring dramatic two-thousand-year-old monuments in the desert, with no admission charges and not another single human being in sight. You can see what life is like in a former backwater of the Soviet empire after the collapse of the USSR - a place that was once a major centre for testing chemical and biological weapons, and was completely out of bounds to foreigners. You can spend a day in a modern museum exhibiting a world-class collection of Russian and Central Asian avante garde paintings. You can see great displays of local ethnic costume and yurts. You can witness the planet's number one environmental disaster zone first hand, with fishing boats stranded in the middle of the desert. And, if you are really adventurous, you can explore what was until recently the World's fourth largest inland body of water – the starkly beautiful Aral Sea - before it finally disappears from the face of the Earth. Of course Qaraqalpaqstan isn't everybody's cup of tea. It demands a curious mind, the confidence to travel alone, and a willingness to take the rough with the smooth. There are no first class hotels; no haute cuisine eateries; no trendy nightclubs; and no pool-side sun loungers.

The traditional culture of the Qaraqalpaqs.

|

|

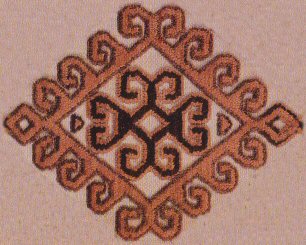

Although the majority of Qaraqalpaq ethnic artefacts now reside in local museums, one important remnant of the former local culture still survives in

the rural parts of Qaraqalpaqstan. A small minority of Qaraqalpaqs still erect and decorate their yurts for the summer, when they are used for

entertaining family and guests as well as for relaxation and sleeping, being much cooler than houses during the unbearable hot summer months. The season is short

– from early June to late August or early September. The first half of June is the best time to see them.

|

One of the local museums, the Qaraqalpaq State Museum of Art named after Igor Savitsky, also houses a world-famous collection of Russian and Soviet

avante garde paintings. The collection was assembled by an eccentric Ukrainian artist who had been invited to come and work in No'kis by a

friend of his family at a time when he was training to be a painter in Moscow. His patron was the famous ethnographer of the Qaraqalpaqs Tatyana

Zhdanko, who had joined up with the Moscow archaeologist Sergey Tolstov, the founder of the famous Khorezmian Archaeological-Ethnographical

Expedition. The young Igor Savitsky first worked as an illustrator, painting a series of local archaeological sites for the expedition, and then

became involved in collecting examples of local Qaraqalpaq material culture, such as embroideries, weavings, and yurt decorations, for the Laboratory

of the Academy of Sciences. In the late 1950s he began collecting paintings from across the Soviet Union – paintings that would have resulted in his

arrest and detention in a labour camp had the authorities in Moscow become aware of them.

The Republic of Qaraqalpaqstan also contains the largest number of important archaeological sites pertaining to the ancient civilization of Chorasmia.

Thanks to our conservative education system with its myopic focus on the classical history of the Greeks and Romans, most Westerners have never even

heard of Ancient Chorasmia, or to use its more modern description, Khorezm. Yet during the second half of the first millennium BC and the first half

of the first millennium AD, this whole region was a thriving agricultural oasis, supported by a huge network of man-made irrigation channels. Its

population believed in the Zoroastrian cult of fire. They were governed by a dynasty of Khorezmshahs who lived in richly decorated palaces and they

were defended from nomadic attack by an elaborate system of garrisons stationed in sophisticated mud-brick fortresses with an advanced military design.

|

|

For the past twelve years archaeologists from Qaraqalpaqstan and Australia have been uncovering the secrets of the massive fortified site of

Kazakl'i-yatkan, founded around the 3rd century BC and later buried under the desert sands. It may have once been the capital city of the region.

In the recent years they have discovered the largest collection of wall paintings ever found in Central Asia in what may have been a temple or

religious palace.

|

Despite almost two thousand years of erosion by winter rains many of these huge fortresses, palaces, and other sites still exist on the fringes of the

Qizil Qum desert. They are readily accessible, yet devoid of vistors. The best place to see them is in southern Qaraqalpaqstan, east of Biruniy and

just south of the Sultan Uvays Dag mountains.

|

Today the region is also famous for one other reason. The Soviets turned Qaraqalpaqstan and its neighbouring regions into a major centre for the

production of cotton, a thirsty crop requiring substantial levels of irrigation. As an increasing proportion of the Amu Darya was diverted into the

inefficient irrigation systems of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Qaraqalpaqstan so the amount of water left over to flow into the Aral Sea began to

dwindle. The Aral Sea has always been a shallow and therefore unstable inland lake surrounded by desert. It loses around one metre of its water level

every summer through evaporation. With its major water supply substantially reduced it inevitably began to contract from the late 1950s onwards.

Today it has lost over 90% of its former water content and has now fragmented into a number of smaller lakes. The contraction of the Aral Sea has

led to the destruction of the local fishing and shipbuilding industries and the modification of the local climate, reducing regional rainfall and

encouraging the desertification of the northern delta. Environmentalists, geographers, and fresh-water scientists regard the Aral crisis as one of the

world's worst man-made environmental disasters. In recent years the region has turned into a laboratory for understanding the consequences of water

mismanagement on an international scale.

|

The easiest place to see the effects of this disaster is at Moynaq, once the main shipbuilding and fishing port of the region. Today the dried-up bed

of the former Aral Sea stretches over the horizon. Just out of town is the eerie "ships' graveyard", with the rusting hulks of fishing trawlers

standing alone as if they had been dropped from the sky into the middle of the desert.

Overseas visitors to Qaraqalpaqstan are remarkably few and far between. The State Museum of Art – visited by virtually everyone who reaches as far

as No'kis – gets only around 1,000 foreign tourists a year. In 2007 the French were the most frequent visitors, followed by the Germans, Italians,

and Swiss, with the unadventurous British and Americans some way behind. Yet tourists flock in their thousands to centres like Samarkand and Bukhara,

rebuilt by the Soviets into fantasy reproductions of their former selves and filled with tourist tack.

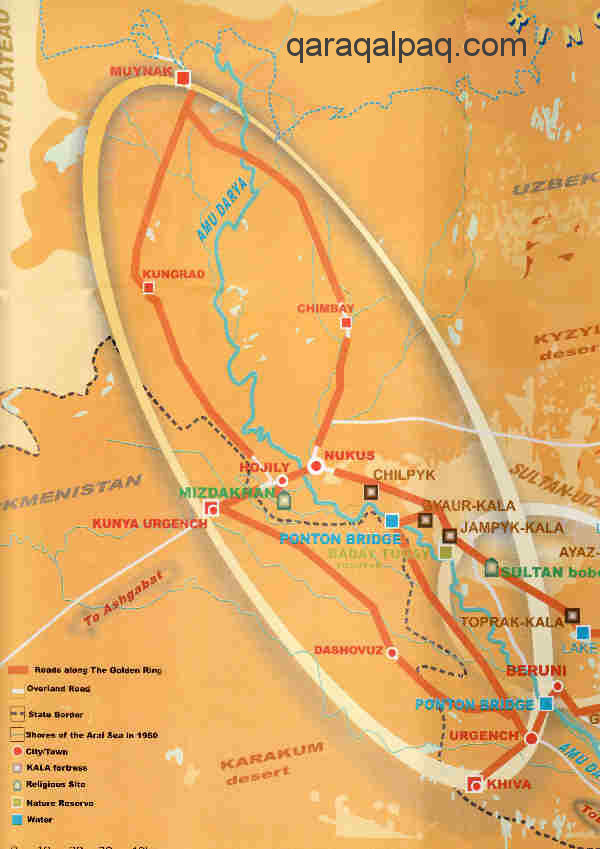

Of course the government of Qaraqalpaqstan would love to encourage more of us to visit their country. With the help of the UNESCO office in Tashkent,

they recently developed the concept of the Golden Ring of Ancient Khorezm – a cultural zone encompassing the region of the lower Amu Darya from Khiva

and Biruniy in the south to Moynaq in the north.

|

Most tourists visit Qaraqalpaqstan as part of a wider tour of Uzbekistan or Central Asia. Many come for just a night or even a few hours, wasting an

opportunity to see a bit more of this fascinating region. Most published tour guides of Central Asia or Uzbekistan treat Qaraqalpaqstan as an

afterthought, sparing just a couple of pages to describe the Savitsky Museum and the ships' graveyard at Moynaq. The purpose of this chapter of our

website is to encourage visitors to stay longer in this interesting region and to see some of the things off the beaten track. Most tourists leave

Uzbekistan with a totally false Walt Disney impression of the country, having been stripped of their dollars by the wily merchants of Samarkand and

Bukhara. In Qaraqalpaqstan it is so easy to meet ordinary friendly people and find out what life is honestly like in a rural part of the "Stans".

Qaraqalpaqstan is totally safe. Like the rest of Uzbekistan, Qaraqalpaqstan is heavily policed, crime is very low, and miscreants who are caught receive

rough justice. There is also no terrorist threat. Unlike Tashkent and eastern parts of Uzbekistan, there is no militant Islamic movement and to date

there have been no incidents of terrorist activity or public disorder.

Qaraqalpaqstan is also a remarkably tolerant destination. Although Western visitors still generate curiosity, especially in rural areas, people are

very welcoming and friendly. Despite being overwhelmingly Islamic in a moderate kind of way, this is a tolerant society where religious feelings

are normally expressed in private.

|

The best times to visit are from late April to early June and from mid-September until the end of October. The spring arrives later in Qaraqalpaqstan

than it does in Tashkent or Bukhara. It can still be cold, grey, and wet in April. Yet by mid-June the daytime temperature is over 40 and sleeping

without air conditioning or a fan becomes quite unpleasant. Many families wait until it gets hot and there is no more chance of rain before erecting

their summer yurts, so you will have to wait until late May if you want to see them.

It is preferable to travel light. Light cotton shirts, skirts, and slacks are ideal for the summer, but a jumper and coat are essential in March, April,

early May, and October. Although there will be few opportunities to dress smartly, visitors should always dress conservatively. This means long trousers

and sleeved shirts for men and sleeved tops and longer skirts or trousers for women. Locals may be too polite to comment on more revealing outfits, but

if you wear them you will lose all respect in local eyes. In the summer, rural parts of Qaraqalpaqstan are amazingly dusty so stout walking shoes are

recommended out of town. A hat with good shade protection and sunglasses are essential out in the open.

|

Finally don't be put off by all the negative comments published about No'kis and Qaraqalpaqstan. These are written by visitors who only stay for one

day and who have made no effort to understand the region or to interact with local people. Even if you only plan to visit for a few days our best

advice is to always stay in a recommended hotel, or with a local family if you possibly can, and to use a local driver/guide, even if you already have

your own Uzbek tour guide.

Have a great trip!

|

This site was first published on 1 April 2008. It was last updated on 8 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2018. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |