Qaraqalpaq Marriage

Western-style marriage costumes became increasingly fashionable during the Soviet era.

A Qaraqalpaq wedding party in No'kis around 1980.

In the late 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th century it was normal for a girl to be married by the age of 15 or 16,

although we have come across one woman who married when she was 30. Most marriages were arranged by the parents while their

children were still young and in a few cases even before they were born. Each clan had its own laws governing the choice of

potential partner and although there were a few exceptions, most clans only permitted exogamous marriage - a woman was forbidden

to marry within her own clan. Since most villages were composed of just one clan, marriage involved leaving both one’s family

and village, even if this meant moving to a neighbouring area.

The groom’s family were obliged to pay a bride price or qalın', to compensate the girl’s family for her loss

and this would be negotiated at the time of the marriage arrangement. In turn the young bride was obliged to prepare a complete

dowry for herself and her new home. Embroidery and weaving were essential female skills and girls were taught them

from an early age. By the age of 6 or 7 a girl could have already begun preparing her wedding dowry, assisted by older female

friends and relatives.

The first wedding ceremony took place in the bride’s village when she was no more than 12 or 13 years old and involved members of her

entire clan. First the young groom was obliged to make ritual gifts, or qa'de, to both the young boys and girls and the old

men within the clan’s awıl. Then a bull, which had been purchased by the groom’s family, was sacrificed and its meat was

divided out among all the families in the village. Following the fulfilment of all the marriage rites the mullah conducted the

official wedding ceremony. On the following day the husband returned to his own village.

The astonishing feature of the Qaraqalpaq wedding was that the young bride continued to live with her parents for up to three or

maybe even five years. Her husband might visit her from time to time, but mostly he lived with his parents in his own village.

The bride was free to make contact with other young men in her village and to participate in feasts and gatherings. In some instances

a local liaison might result in a bride becoming pregnant and giving birth. Such events were not frowned upon and the husband

generally adopted the illegitimate child. Soviet ethnographers have interpreted this phenomenon as a relic of a former ancient

matriarchal tradition. Whether or not this was the case, we do know that in many former nomadic societies such as the Saka, the

Sarmatians and the Qipchaqs, women had the same status as men, held positions of power and leadership, and became involved in military combat.

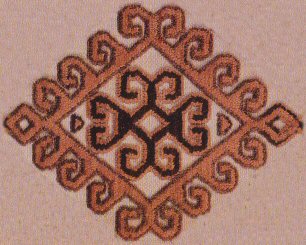

It was during this interim period that the serious work of completing the dowry took place. It was traditional to assemble a

bes kiyim (literally five items of clothing): such as a dress or ko'ylek, coat or shapan, qızıl kiymeshek,

cloak or jegde, and silk turban or tu’rme, along with all of the items for the yurt. The qızıl kiymeshek

was the star item in her dowry and she would begin its preparation with a prayer. A girl might also embroider an aq kiymeshek

or an aq jegde as a gift for her future mother-in-law.

The payment of the qalın' was the necessary condition for the marriage to be concluded. After this the bride could move to her

husband's village and begin life as a married woman. The final wedding ritual (neke qıyıw) was often a two-day affair, commencing on

an auspicious day like a Wednesday. On the first day the young bride would say goodbye to her family and friends and with the

accompaniment of special farewell songs would depart in a donkey cart for her husband’s village. Just before entering her future

father-in-law's home she was dressed in her kiymeshek, helped by a proxy mother (murındıq-ene) who had been selected

to act as her mentor. Every single hair on her head had to be hidden.

At the u'yleniw toy or main wedding feast, later the following day, the bride remained out of view in her kiymeshek behind

the shımıldıq wedding curtain in her father-in-law's yurt or mud-brick house (tam). Then the bride was presented to

the husband’s family and village, her face covered by a white veil. After a short speech by a respected male elder her face was revealed

to the crowd, a ritual known as the bet ashar (revealing the face). The bride would then present gifts to the village elders

and youngsters within her new village. Later a local mullah or iyshan would bless the couple. If she were lucky,

she and her groom would spend their wedding night in a bridal yurt, or otaw, provided by the groom's parents but decorated with

weavings from her dowry. Otherwise she would sleep in the home of her new family but behind the privacy of the wedding curtain.

In a very wealthy family a wedding could be a spectacular event with the bride dressed in five layers of clothing. In the 19th century it

was traditional for the bride of a rich father to be dressed like a princess. She would wear a cross-stitch embroidered ko'k ko'ylek,

or blue dress, a kiymeshek that at that time was probably white, and a stunning sa'wkele headdress. The sa'wkele

was commissioned by the bride’s father and became part of her dowry.

This style of dress seems to have died out by the beginning of the 20th century and the qızıl kiymeshek became the main item of

wedding costume for the Qaraqalpaq bride, topped with colourful turbans.

The life of a Qaraqalpaq bride at that time was not necessarily a happy one. From now on she effectively did the majority of the work in the home of her mother

and father-in-law. It was important for her to show respect and deference to members of her new family and custom forbade her to address her mother-in-law,

father-in-law, or brothers-in-law by their proper names - their titles were used instead. The majority of brides would live in their father-in-law's

home for many years. Although many marriages were happy and successful there were also many situations where young wives fled back to the parental home.

Even then the wife would be encouraged to return to avoid the repayment of the qalın'. There were also frequent cases of murder and

suicide. When Rossikova visited the southern part of the delta in 1901 she mentioned that hanging was the most common way for women to commit suicide.

In his poem Kelin ("Daughter-in-law") the famous Qaraqalpaq poet Berdaq, living in the 19th century, vividly described the fate of a Qaraqalpaq girl,

sold into the house of her husband for cattle.

"... I was purchased as goods,

For a pitiful fifty tuwar.

Evil father, but he is already old".

Nowadays it is far more common for young people to choose their partners themselves, though obviously with the help and advice of their relatives.

The official "House of Happiness" in No'kis where marriages are formally registered. Early 1980s.

Following the imposition of Soviet control traditional customs were frowned upon by officials and religious leaders were persecuted. Campaigns

were organized to endorse women's rights and to discourage the wearing of jegdes and kiymesheks. The payment of the

qalın' became illegal. At the same time Russian Western-style dress became fashionable and was seen as an expression of status.

By the end of the Great Patriotic War traditional Qaraqalpaq wedding attire was a thing of the past and brides aspired to a Western-style white wedding.

However the old ways have not been forgotten. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the tradition of the qalın' has

returned, as has the blessing by the mullah, although the Western-style of wedding continues.

Pronunciation of Qaraqalpaq Terms

To listen to a Qaraqalpaq pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

![]()

![]()