Sightseeing in Qaraqalpaqstan - Part 2

|

Sightseeing in Qaraqalpaqstan - Part 2

|

|

ContentsPart 1Walking TourThe Cathedral Mosque Museums Local Bazaars Shopping Part 2Iyshan qalaYurtmaking at Shımbay Moynaq Qazaxdar'ya Birdwatching and Wildlife Badai Tugai Nature Reserve Ustyurt and the Tchink Aral Sea Expedition Google Earth Coordinates Iyshan qalaIyshan qala is the site of an abandoned 19th century Sufi centre, consisting of a single-storey mud-walled mosque and medresseh. Run by an iyshan, a Sufi religious leader, it instructed young boys in the teachings of the Qu'ran. The site was abandoned following the Soviet religious crackdown of the 1930s. This is one of the few remaining buildings in the lower Amu Darya region that has a traditional 19th century style of construction. At that time the majority of wealthy farmers lived in ha'wlis, mud-walled enclosures that contained a house and a garden. Just as here, the walls and conical corner buttresses were normally decorated with geometric zigzags and patterns.

The decorated outer walls of Iyshan qala.

Interior of the mosque.

Quwanıshbay (third from the left in the back row) with some of his craftsmen.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Quwanıshbay decided to become a yurt master after secondary school and began to make his own yurts in 1970. Today he employs eleven local

craftsmen. It is a precarious profession. The modern demand for yurts is minimal and uncertain. The workshop scrapes by on the back of a handful of

orders a year. Some years ago he made the yurt now displayed inside the Savitsky Museum.

Quwanıshbay is happy to show the odd visitor around, although you may need to ask directions to find him. Hopefully you will reward him for

his troubles.

For more details see our webpage on Yurtmaking.

Moynaq

A visit to Moynaq comes high on the list of priorities for most visitors to Qaraqalpaqstan. It takes over three hours to get there from No'kis, so

its advisable to leave early and to make a full day of it. It is 90km to Qon'ırat as the crow flies and a further 80km to Moynaq. There is

supposedly a Korean restaurant in Moynaq but don't gamble that it will be open. Buy some sausage and cheese the day before and stop off at

Qon'ırat bazaar for some fresh bread, tomatoes, and cucumber. The region between Qon'ırat and Moynaq is a complete wilderness, with the

roadside dotted in summer with patches of colourful local Aral flora, including liquorice and tamarisk.

|

|

At Aral awıl you can see typical Qaraqalpaq homesteads with the cattle kept in brushwood qoras or mal qoras. The

fencing is made from bundles of rushes, laced together at the top. Stacks of tall rushes stand around drying outside the farmsteads. Early 19th

century travellers to the delta described northern Qaraqalpaq villages as "cities of reeds".

|

Some people find the trip to Moynaq depressing. We think that it is still a jolly little place, retaining the air of a seaside town even though the

shore of the Aral Sea is 80km away and receding. Mind you, we don't have to live there and scrape a living. It is hard to understand how this small

community still survives following the destruction of their economy. We sometimes think how angry we would be had we grown up there as children in

the 1950s, looking back now to see how our lovely environment and way of life had been stolen from us, never to return in our lifetimes.

|

The Qaraqalpaq water authorities have responded to the growing Aral crisis by preventing any further wasteful outfall, preserving precious water stocks

in a sequence of large lakes crossing the northern delta. These have been stocked with freshwater fish to maintain a semblance of the old fishing

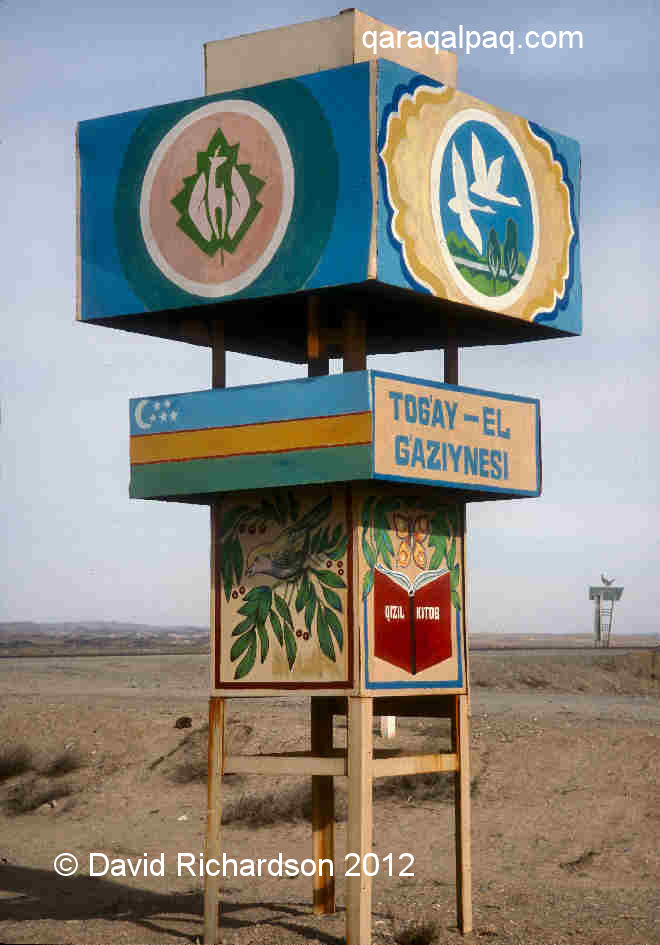

industry. You will see one of these lakes as you approach the town. The nostalgic Moynaq road sign harks back to the town's seafaring past with its

decorative fish and seagull.

|

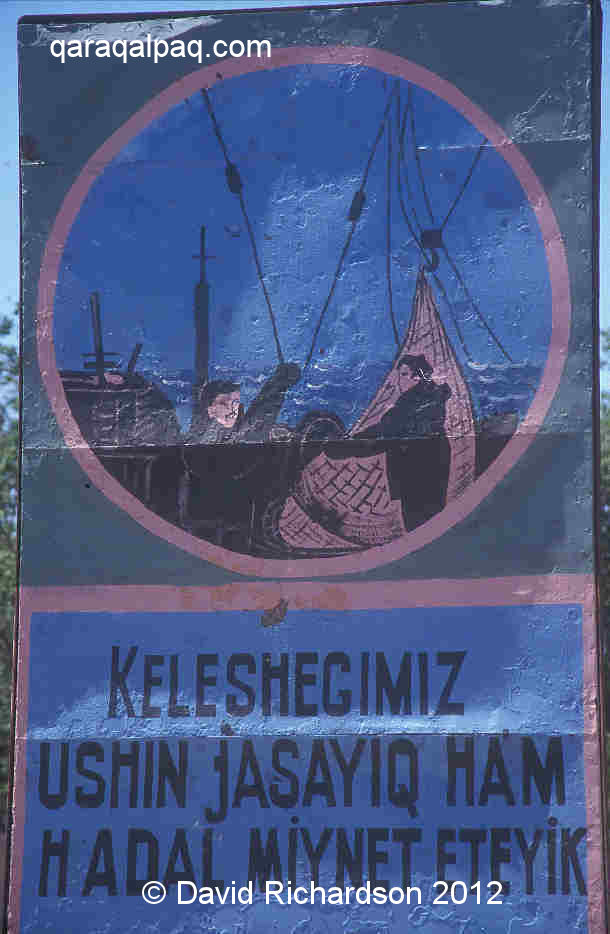

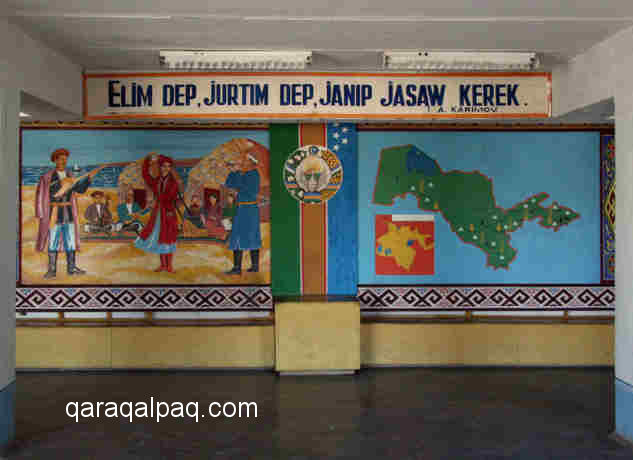

Almost everything around Moynaq is a reminder of the Aral Sea. The main street is lined with posters relating to the Aral disaster and halfway along

it is the old fish canning factory surrounded by railings. Next door is a fishing boat mounted on a pedestal. Across the road is Moynaq Museum, run

by a young and helpful curator, which is well worth a visit. The problem is that it is frequently closed; not surprising given that it only gets one hundred

foreign visitors a year.

|

|

|

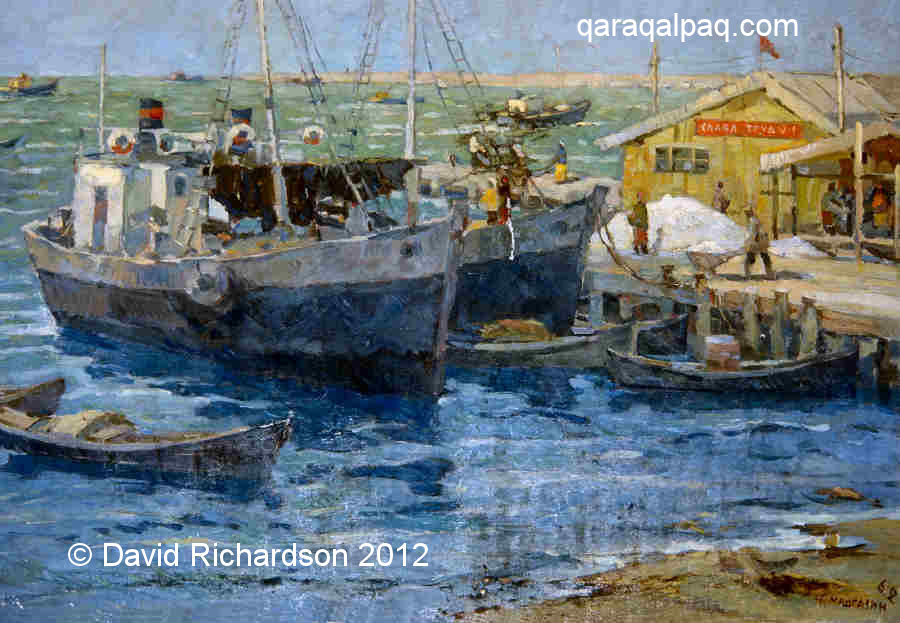

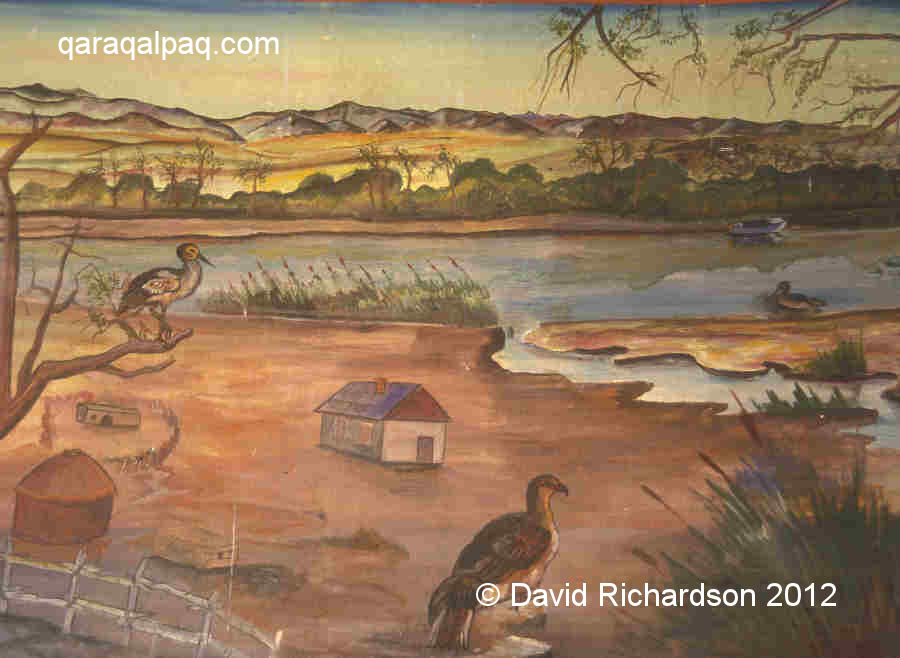

The exhibits are displayed in a large room lined with paintings of the old Moynaq and U'shsay ports in their heyday. There is a local rowing boat with

angled water guards, anchors, nets, baskets, fishing hooks, a few looms and scraps of textile, examples of local furs such as badger, cat, wolf, fox,

and muskrat (fur-farming was a local industry), and a display of how they used to make jeken (bulrush) mats. The museum has some wonderful

albums of black and white photographs donated by the fish-canning factory and taken in its heyday before the collapse of the fishing industry. There

are also old colourful tins of Moynaq canned fish, labelled "Bream", "Carp", "Pike-Perch" and "Sheat". The museum is in a decrepit state, with

preserved fish only half covered in formaldehyde, rotting stuffed birds, and paintings stained with water from the leaking roof. Sometimes the museum

has paintings for sale by local artists.

|

Continue along the main road as it sweeps round to the left, until you reach the Berdaq Cinema on the right with a silver bust of the bard standing

out in front. Continue straight on, zigzagging through a residential area. On the right you will soon see a long high shingle bank running parallel

to the road. This is the backbone of the former island of Toqmaq Ata. At the end of the road you curve down to the small settlement of U'shsay. This

used to be the main cargo port of Qaraqalpaqstan, with cotton arriving by rail to be shipped across the Aral Sea to the Qazaq port of Aralsk. Today

it is a stepping stone to the natural gas field lying below the former seabed that has only just been drilled in recent years.

Drive back to Moynaq and turn left just before the Berdaq Cinema. This road leads you to the Great Patriotic War memorial, a white triangular sail

emblazoned with the Uzbek flag perched on the edge of a cliff. As you look out across the wide expanse of flatness stretching to the horizon in front

of you it is easy to imagine that it is still the sea rather than scrubby white desert.

|

The so-called ships' graveyard lies off to your right. To get there, drive back to the main road and turn left past the cinema. Immediately fork

left down a small side road and fork left again onto the track that leads out across the old beach. You can park by the old shoreline and walk to

the rotting hulks of the fishing boats, which are positioned in groups. One of them looks in remarkably good condition - it is the "Qaraqalpaqia".

Some years ago it was painted grey by a Polish film crew as a backdrop to their movie.

|

It's hard to imagine the circumstances that led to the stranding of so many boats on the shoreline. The underlying cause was the increasing demand

for cotton under the Soviets. Cotton is a water-intensive crop and the continued expansion of inefficient irrigation networks along the Amu Darya

resulted in less and less water reaching the Aral Sea. The final act was the opening of the Qara Qum canal, diverting almost one third of the water

of the Amu Darya into Turkmenistan to support its own expanding cotton acreage. At first the decline in the level of the Aral Sea was small because

of compensating inflows from the numerous delta lakes and the surrounding water table. Some of the first people to recognize that there was a problem

were the Aral fishermen themselves, who noticed that the level of the highest tide kept falling relentlessly from 1964 onwards. Soon the port at

Moynaq began to dry up and Toqmaq Ata Island gradually became connected to the mainland.

|

It used to be possible to visit the old retired harbourmaster, Sergey Epatyevich, in his little Cossack house in the town centre before he moved to

Russia several years ago. He described how in 1968 they were forced to relocate the boats from the fishing port at Moynaq to the cargo port at U'shsay.

In time this also began to dry out and channels had to be cut to allow the boats to reach the Sea. It turned into a traumatic and hopeless battle –

Sergey said at times he felt like hanging himself. The local seamen battled on until 1983 when they finally abandoned their fishing. By then the

ferry service had terminated and the bigger fishing boats had become stranded on the dried up seabed. Thanks to Soviet economic madness the fish

cannery continued to function, by bringing in frozen fish by train from the Caspian and the Barents Sea.

|

By 1989 the population of the town had halved to 12,200.

Minvodkhoz, the Soviet Ministry responsible for irrigation and canals, responded by proposing the construction of a massive Sibaral canal,

designed to drain water from southern Siberia into the Aral Sea. It was one of the first projects to be scrapped by Gorbachev after he came to power

in 1989.

The rusting hulks that remain today are only a fraction of the original fleet, many having been completely dismantled for scrap.

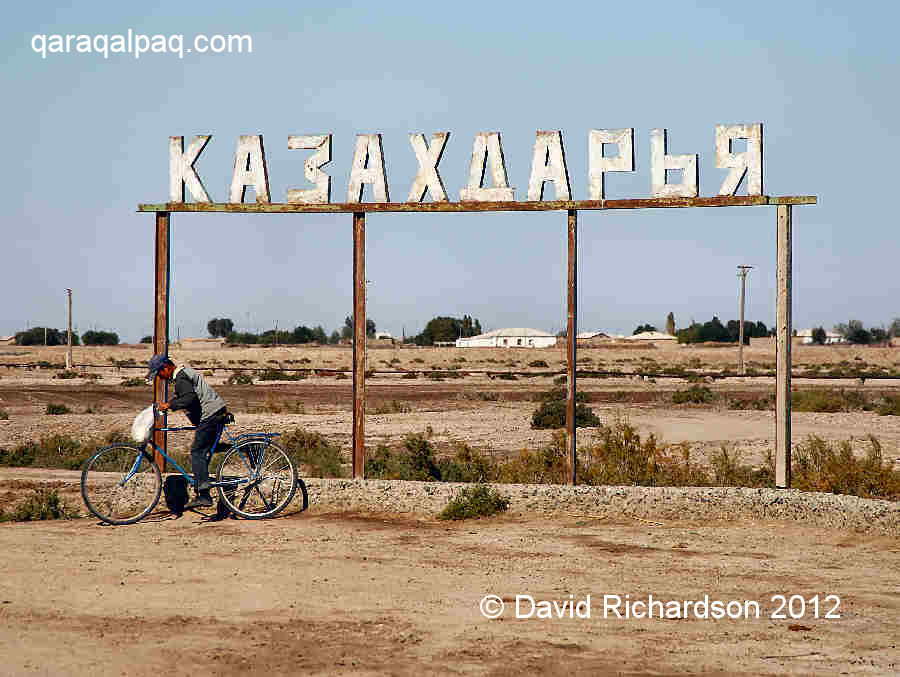

Qazaqdarya

To see another side of the Aral crisis take a trip to Qazaqdarya, about 125km north of No'kis. Drive to Shımbay and take the left fork

to Shaqaman. Just before Shaqaman you will get a glimpse of the eastern edge of the so-called Qusxanataw hills. This is a slightly raised region

of desert, about 20km wide from east to west containing a central salt lake. The unendingly straight road beyond Shaqaman enters a different

wilderness as flat as a pancake.

|

The village of Qazaqdarya stretches out to the right and the left of the road following the banks of a canal. As its name suggests it used to be a

Qazaq settlement, positioned by an inlet of the Aral Sea. There was a big local fishing industry, along with a fish smokery. Many Qaraqalpaqs came

to work in the fishing industry and today the settlement is 50% Qazaq and 50% Qaraqalpaq. Of course the Aral Sea is long gone and today the whole

area looks like the face of another planet.

|

|

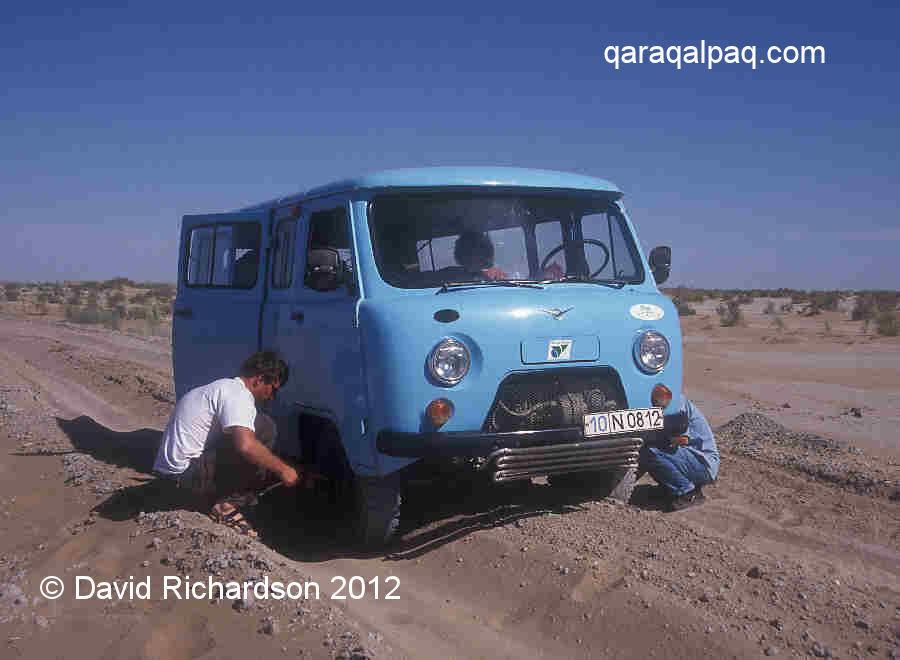

The soil is white with salt and you can see several redundant boats perched high and dry on the canal bank. The whole region north of the village is

a barren desert. You can drive into it for about 15km until the road surface disappears. With a 4WD you can explore the whole area, which is popular

with local hunters looking for wild boar. Some 40km north of Qazaqdarya is Aq qala, an old Khivan fort that was once located besides an outlet of

the Amu Darya.

|

In the 1950s this was a thriving community and almost every home had a yurt. The disappearance of the Aral Sea has modified the local climate,

reducing the incidence of rain, especially during the spring growing season. Of course the salt is a natural phenomenon associated with any large

inland basin, but as the irrigation channels have dried up it has become impossible to wash it away. The whole region has turned into a desert.

Today the residual community are hanging on by their fingernails. There is still some livestock farming and fish are caught in the local lake. The

children have a big school, there is a German aid project trying to use modern technology to grow wheat, and there is even a local mobile phone mast!

As a reminder of the past, a handful of homes still erect their yurts in the summer, which you will be welcome to visit. On the edge of the canal

lying to the west of the main road you can see a crude waterwheel powering a small irrigation pump. At one time the whole region was watered by

shigir waterwheels powered by blind-folded camels and donkeys.

Birdwatching and Wildlife

Up to the early 20th century the marshes, lakes, and shorelines of the Amu Darya delta supported a vast population of birds and other wildlife. The

artist Nikolay Karazin was one of the first foreign civilians to see the delta, having arrived after the fall of Khiva in 1873 on a Russian paddle

steamer from across the Aral Sea:

"Above the surface of the water the reeds reach seven arshins in height [5 metres]; ... Thousands of birds tweet and twitter in these shady thickets; here, there and everywhere is black with their shaking nests ... Large noisy pelicans fly out from the thicket and come down to swim in the open areas; graceful swans touch the bottom after extending their long neck, catching the air with their wings ... Pale blue bee-eaters, like a turquoise dot, shake and sparkle in the air, swaying after landing on the tip of a stem only the thickness of a finger ... Noisy clouds of rose-coloured starlings arrive, flying in from the coast to hunt the midges and mosquitoes ... Life not only boils above the water, it boils below the water as well: huge catfish float almost to the surface like motionless logs, turned black in the calm transparent water; they idle in whole shoals, small fishes sport, and only the noise of the steamer wheels and the clicking ring of the tow-rope disturbs this entire population, driving it away into the very depths of the impassable thickets where no "devil boats" can reach."

|

Today the Amu Darya delta is primarily a land of crows and magpies. Intensive agricultural development from the 1920s onwards has changed the region

irrevocably, while more recent desertification has drastically reduced the number of avian habitats. As such we cannot recommend Qaraqalpaqstan as

a birdwatching destination. However for those birders who have come for another reason it is still possible to spend an interesting day looking for

birds.

|

One of the best destinations is Moynaq. One place to look is around the freshwater lake at the entrance to the town, but the best location is close

to the ships' graveyard where there are many small brackish pools, ideal for waders. Despite being mere amateurs we have personally spotted: dunlin,

little stint, common sandpiper, purple sandpiper, Terek sandpiper, redshank, ruff, turnstone, oystercatcher, black-winged stilt, glossy ibis, shelduck,

little egret, grey heron, herring gull, common tern, arctic tern, pheasant, blue-cheeked bee eater, wheatear, crested lark, hoopoe, hooded crow, common

mynah, and several different harriers.

|

The most exciting place to watch birds is along the beach sandwiched between the western shore of the Aral Sea and the tchink. This acts

like a wildlife corridor, channelling migrating birds into the Amu Darya delta from to Kazakhstan and Siberia. At the waters edge you will find gulls

and many shoreline wading birds such as common sandpiper. The small bushes provide shelter for passerines and if you are lucky like us, you may see

sparrowhawks and golden eagle hunting along the cliff tops. Up on the barren Ustyurt there are a surprising number of pipits and skylarks.

|

For a bird list of Uzbekistan click here.

There is even a Qaraqalpaqstan bird guide although it is written in Russian: "Birds of Qaraqalpaqia and Their Conservation", by M. Ametov, No'kis, 1981.

|

The region to the north of Qarao'zek and Taxta Ko'pir lying south of the former Aral coastline used to be inhabited with many Qaraqalpaq

awıls. Today it is an empty wilderness, popular with local hunters. To gain access you need a 4WD vehicle, but the region is readily

accessible from No'kis and offers an interesting day out for those looking for solitude. There are certainly wild boar, hares, foxes, and lizards.

|

The Ustyurt is famous for its large herds of saiga antelope (Saiga tartarica), which migrate south from Kazakhstan to winter on

the plateau. However some must be resident throughout the year as we have seen many saiga on the Ustyurt in June. Saiga have a

distinctive snout-like nose, evolved to filter dust so they can breath when moving in huge herds, many thousands strong. They are known locally as

aq quyrıq, meaning white tail. Saiga are shy creatures and hard to get close to. Not surprising as they suffer badly from poaching,

especially in Kazakhstan but also in Qaraqalpaqstan. They are not only hunted for their meat but also for the horns of the male, which poor Qazaq

farmers can sell for up to $100 a kilo, thanks to insatiable demand from China, Malaysia, and even Tibet and Mongolia. However in Qaraqalpaqstan,

where the poachers tend to be either unemployed or seasonal workers, the motivation is primarily for food. It has been estimated that the Ustyurt

population has crashed from 200,000 in the mid-1990s to less than 15,000 today, turning the saiga into a threatened species. Their conservation has

now become a priority, although the sums available for their protection are pitiful.

Saiga antelope have been hunted on the Ustyurt probably since the Neolithic. In the 1980s archaeologists led by Vadim Yagodin at the Academy

of Sciences in No'kis became fascinated by the huge arrow-shaped structures dotted around the edges of the Ustyurt. They were known as kites,

because that was the shape that they looked like to airline pilots flying over them, although the local people referred to them as arans. They

turned out to be huge hunting traps, designed to funnel the migrating saiga into small enclosures where they could more readily be killed. The traps

have been dated from the first millennium BC to the time of the Golden Horde in the 14th century AD.

|

Another unusual mammal that was once common on the Ustyurt is the goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa), whose population has also

been badly affected, in this case by the construction of the Bukhara-Urals gas pipeline and by more recent natural gas exploration. There is now a

small Ustyurt population of only a few hundred living close to the Sarykamysh Lake on the Qaraqalpaq-Turkmen border.

The rare Bukharan red deer is being conserved in the Badai Tugai nature reserve in southern Qaraqalpaqstan - see next section.

|

In the more remote areas of Qaraqalpaqstan it is possible to see hares, badgers, desert fox, ground squirrel, jackal, and pole cat. Small snakes and

lizards are common in the desert.

Badai Tugai Nature Reserve

Formed in 1971, the Badai-Tugai Zapovednik is a scientific nature reserve located on the northern bank of the Amu Darya about 20km west of

Biruniy. The reserve is signposted on the main A380 to No'kis. The reserve's objective is to preserve and study one of the few remaining zones of

tugay flood-plain forest that at one time extensively covered the whole region. The reserve extends over about 6 square kilometres.

|

Tugay forest is actually a complex ecosystem composed of a number of adjacent related habitats growing away from the water line: shoreline

communities giving way to reedbeds, then gallery forests, then fringe shrubs, sedges, and finally desert. In the past poplars and willows dominated

the dense forests, while tamarisk and elaeagnus filled the shrub thickets. This dense vegetative cover used to provide habitats for a rich spectrum

of wildlife: birds, waterfowl, large and small mammals, amphibians, and in the spring and summer, huge quantities of mosquitoes. Over the past 50

years the whole environment of the delta has changed beyond recognition. The former flood plain of the river has been intensively developed for

irrigated agriculture, with the water table significantly lowered, and the seasonal floods artificially controlled. Now the water supply for the

forest comes mainly from ground water, partly fed by the river and partly fed from wastewater from Biruniy. The reserve is not only compromised

by the severe condition of the Amu Darya but also by its proximity to the Aral Sea.

|

The Badai Tugai reserve contains jackal, steppe cat, fox, and the reintroduced Bukharan red deer. The latter is a severely endangered species, its

total population having fallen to just 350 by 1998-99. The numbers at the reserve have been steadily recovering, reaching about 160 in 2007. Some

have been used to reintroduce the species into the Zeravshan river valley. Of course the deer are not confined to the reserve but migrate in and out

of the forest.

The Badai-Tugai reserve is also well known for its population of pheasants.

The reserve centre has simple overnight accommodation for up to 10 people. Visitors are advised to use anti-mosquito protection.

Ustyurt and the Tchink

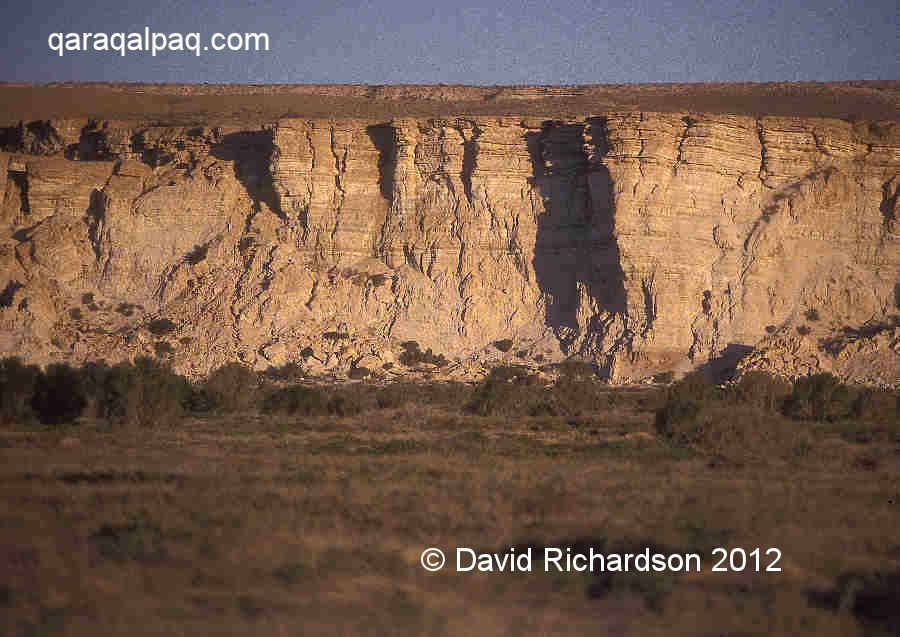

The Ustyurt is an extraordinary natural geological feature, a sand and limestone desert plateau stretching 800km from north to south. It sits

on its own micro-tectonic plate or massif which has been gradually elevated over the past four or five million years so that it now stands around 200

metres higher than the delta plain. Geologists have found that it is continuing to rise at a rate of about 1cm per annum. Its top is protected from

erosion by a layer of Sarmatian limestone. In places this has been eroded by acid rain to create complex cave systems.

|

The precipitous cliff edges of the plateau are lined with huge boulders and landslide debris caused by past tectonic activity. Since the Neolithic

era the Ustyurt has always been the realm of the nomad. However its steep cliffs, referred to as the tchink by the Russians, made it

impossible to descend from the plateau on horseback except in one or two particular locations. As a consequence the tchink provided Chorasmia

with a defensive "Wall of China" for all of its early history, protecting it from nomadic attack in the west.

|

It is a barren and fairly featureless place. In summer temperatures can reach 42°C and in the winter they can fall to -40°C. Coupled with a strong

inshore or offshore wind it can feel in the summer like being in the permanent blast of a hot hairdryer.

|

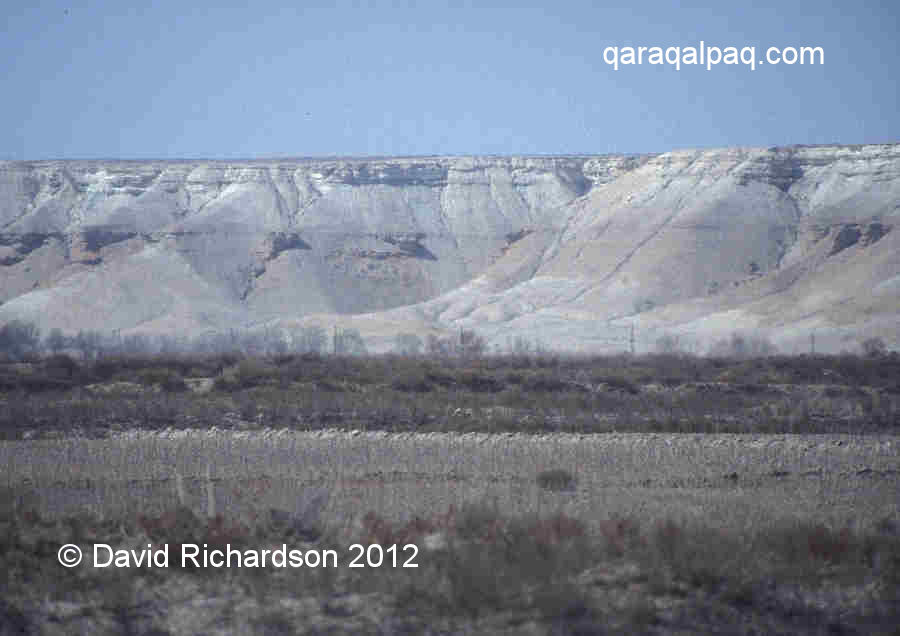

You will see the tchink like some white, dream-like apparition along the horizon as you drive to Qon'ırat. For a closer view, the

easiest place to head for is Shomanay. Continue through the town heading towards the north-west. There are a few Yomut Turkmen living in this area

and some of them have yurts. Just after Sha'ma'mbet you get an excellent view of the plateau. To get even closer, drive further east to one of the

local kolxozes such as Ayjan or Tajenay. It is hard to reach the foot of the tchink because the area is criss-crossed with canals,

but you can get close.

Aral Sea Expedition

The most exciting trip you can make in Qaraqalpaqstan is a visit to the Aral Sea. Despite the decimation of the Aral Sea during the last half century,

the shore of its deeper western basin has only receded by a few hundred metres and remains relatively easily accessible. This part of the Aral is

likely to survive longer than the shallower eastern and central regions.

An expedition to the Aral shoreline requires planning, not because it is a long way to go but because it is potentially dangerous. Firstly the region

is devoid of humanity so if your vehicle breaks down or you get stuck in sand you are stranded. There is no coastguard nor any other emergency service.

Maintenance people occasionally inspect the gas pipeline, but this is located well away from the tchink. Furthermore the route along the eastern

edge of the Ustyurt is not a single road but a wide network of interweaving tracks and although cars and trucks do occasionally pass – this is

after all a smuggling route from Kazakhstan – it would be very easy to miss them. Two vehicles are therefore essential. Secondly you need to take

camping equipment and sufficient water, food, and gasoline with you - even wood if you want a camp fire. Moynaq and Qon'ırat are the last places

where you can obtain fuel and provisions.

An experienced guide is recommended, especially if you are stopped and questioned by the road police.

|

There are two main routes onto the southern Ustyurt. The first is via Moynaq and U'shsay, following the temporary roads established by

Uzbekneftegaz in 2004-05 when it was drilling in this region. These take you towards the two locations on the tchink where it is

possible to drive up onto the plateau with a 4WD - see Google Earth Coordinates. It is a hairy ascent, not recommended

in rainy weather. It is a good idea to spend your first night camping below the Ustyurt if only for the fabulous sight of the illuminated cliff

face at sunrise.

|

The second route, which is easier but less interesting, is to drive directly onto the Ustyurt from Qon'ırat. This requires passing

either the police barrier north of Ravshan or the police post just before the new soda plant (no barrier). The track runs first to the gas maintenance

depot at Komsomolsk-on-Ustyurt and then on the manned microwave repeater station. From here you are on your own.

|

At first the sea is out of sight – it seems that you are already too late! Relax, as you get beyond Cape U'lkentumsıq the southern shoreline comes

into sight. Soon you see the magnificent sweep of the bay bending round to the promontory at Cape Aqtumsıq. As you head north you may pass old

nomadic burial sites. Cape Aqtumsıq is a good place to stop or to camp. You can walk down to the beach using an old track just south of the point

that passes through a landscape of rust and yellow sulphurous soils scattered with large evaporite crystals, clear signs of past volcanic activity.

It is about a one kilometre walk across the beach to the shoreline, but don't expect a swim – the water's edge is soft and muddy and difficult to

stand on.

|

About 90km further north is the beautiful Cape Duana. This is the site of the old Soviet ferry port to Aralsk-7, the biological weapons testing

station on Vozrozhdeniye Island. The low-lying island is now a peninsula, visible along the horizon. There is a broken concrete road down to the beach.

Duana is the location of a complex of ancient kurgan burial sites and several nomad sanctuaries. Professor Yagodin believes that the latter were cult

centres where the nomads conducted rituals before setting off on their seasonal hunt.

|

To the north, the border between Qaraqalpaqstan and Kazakhstan is apparently unmarked. Even so stay well away and do not attempt to make an unofficial

crossing. The newly independent Central Asian States are fiercely protective of their borders and illegal entry is considered a serious offence.

|

Those planning such a trip might gain inspiration from the Paris-based Aral Sea specialist, Professor René Létolle, who was a member of an

expedition to circumnavigate the Aral Sea in 1998. To see his report click here.

The expedition obviously crossed the border from Qaraqalpaqstan into Kazakhstan and back again, only possible because they took immigration and customs

officials from both Republics with them.

Google Earth Coordinates

Qaraqalpaqstan is particularly well served by Google Earth, with the exception of Shomanay and Taxta Ko’pir.

To help with the planning of your trip, the following reference points (in degrees and digital minutes) will enable you to locate each of the following places.

Note that these coordinates come from Google Earth and are not GPS measurements taken on the ground:

| Google Earth Coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Place | Longitude North | Latitude East |

| Independence Monument | 42° 27.623 | 59° 37.081 |

| Savitsky Museum | 42° 27.935 | 59° 36.746 |

| Central Bazaar | 42° 27.706 | 59° 36.242 |

| Jipek Joli Hotel | 42° 28.020 | 59° 36.701 |

| No'kis Hotel | 42° 27.631 | 59° 36.877 |

| No'kis Railway Station | 42° 26.281 | 59° 38.539 |

| No'kis Airport | 42° 28.907 | 59° 37.027 |

| Iyshan qala | 42° 40.046 | 59° 43.782 |

| Xojeli Bazaar | 42° 25.010 | 59° 26.525 |

| Xojeli Mal Bazaar | 42° 25.412 | 59° 24.292 |

| Shımbay Bazaar | 42° 55.921 | 59° 46.357 |

| Qon'ırat Bazaar | 43° 2.973 | 58° 49.996 |

| Moynaq Museum | 43° 46.000 | 59° 1.724 |

| Moynaq Cinema | 43° 47.006 | 59° 1.861 |

| Moynaq War Memorial | 43° 47.411 | 59° 1.975 |

| Moynaq Ships' Graveyard | 43° 46.396 | 59° 2.777 |

| Qazaqdarya Bridge | 43° 25.280 | 59° 38.993 |

| First ascent up onto the tchink | 43° 44.881 | 58° 20.417 |

| Second ascent up onto the tchink | 43° 51.202 | 58° 19.976 |

|

This site was first published on 1 April 2008. It was last updated on 7 March 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2018. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |