The Golden Horde

|

The Golden Horde

|

|

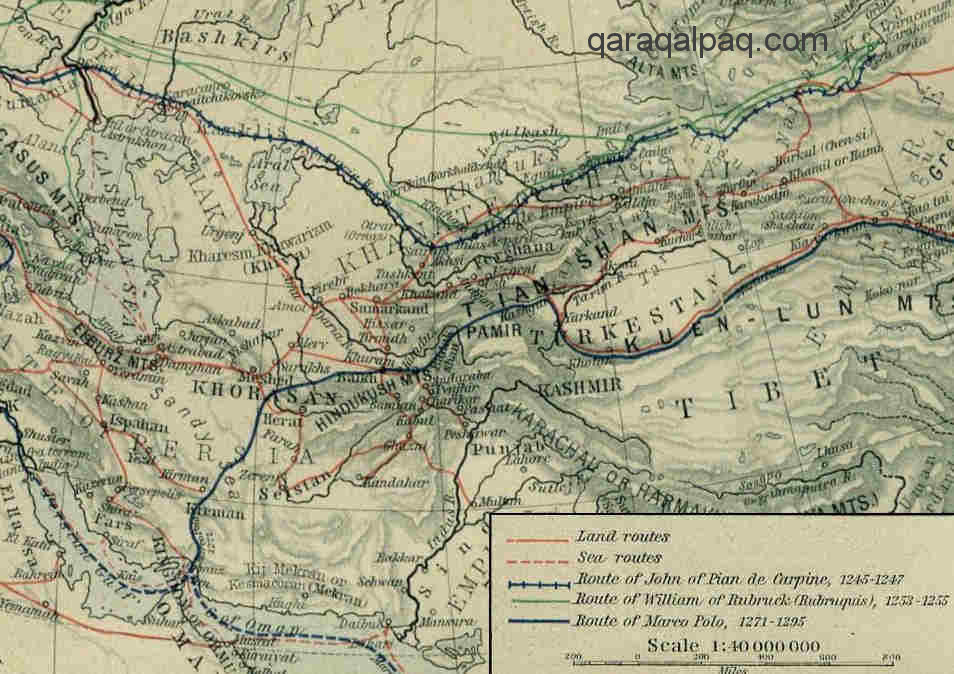

ContentsThe Conquest of Russia and Eastern EuropeThe White, Blue and Grey Hordes Batu's Khanate of Qipchaq Berke Seizes Power Emir Noghay and Toqta Khan Özbeg Khan The Khanate of Qipchaq in the 1330s References The Conquest of Russia and Eastern EuropeIn 1229 Ögedey became the new Mongol khaghan or Great Khan, inheriting his father's administration and imperial guard.

Painting of Ögedey Khan.

He located his ordos in the region of the upper Orkhon and the Qaraqorum Mountains, a region that may have been chosen as the location for

Chinggis Khan's yurt or main encampment some ten years earlier and was now part of the ulus of Toluy. It was primarily the spring

residence of the Khan, the summer being spent in a Kitayan latticed pavilion in the mountains and the winter being spent further south on the Ongiin

River. It would be later, in 1235, that Ögedey would use Kitay craftsmen to build a royal palace at Qaraqorum surrounding it with a

perimeter wall. Ögedey called it Ordu Baligh, the City of the Ordos, although it has subsequently become known as Qaraqorum.

The modern setting of Qaraqorum.

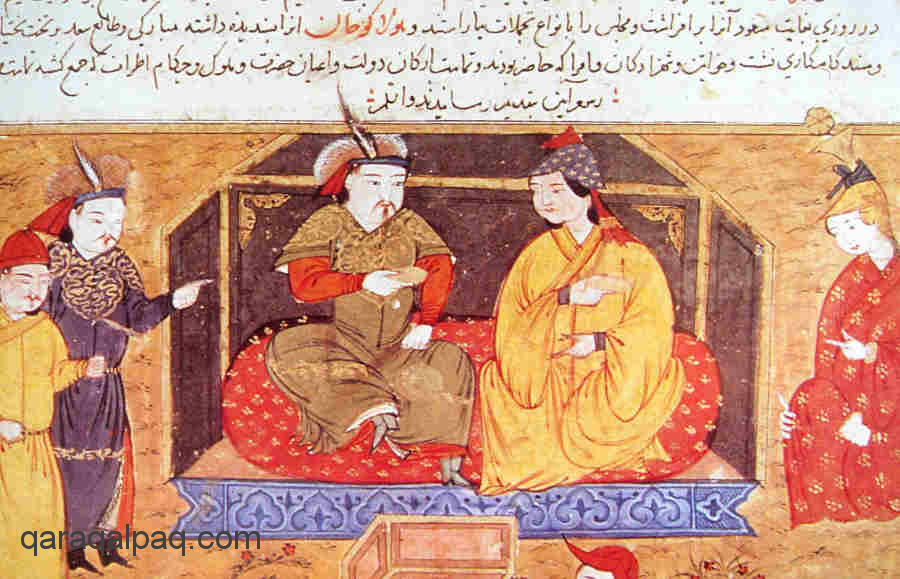

The successors of Chinggis Khan.

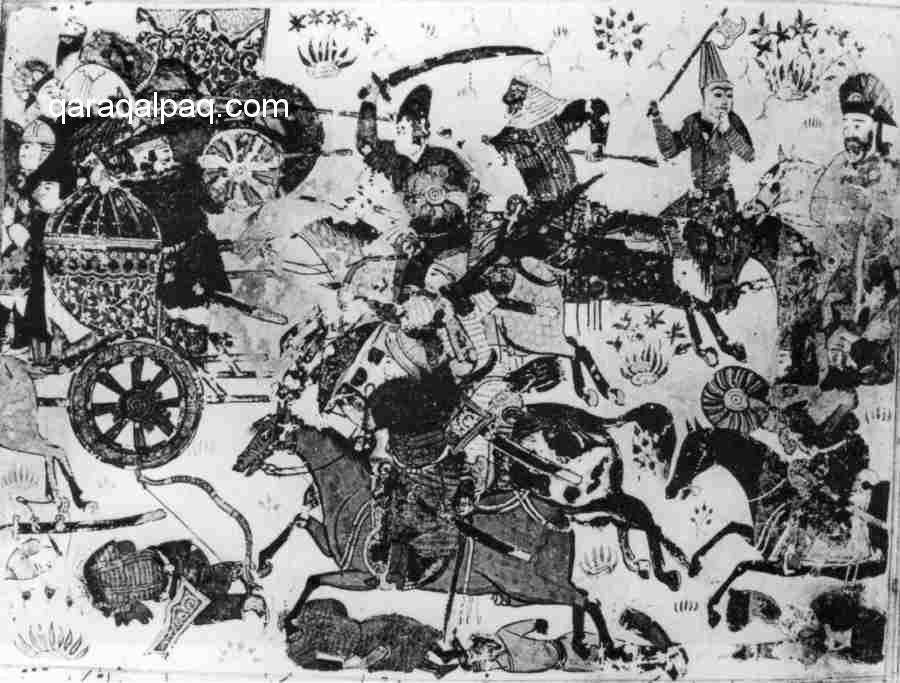

A Persian miniature painting of a Mongol battle scene.

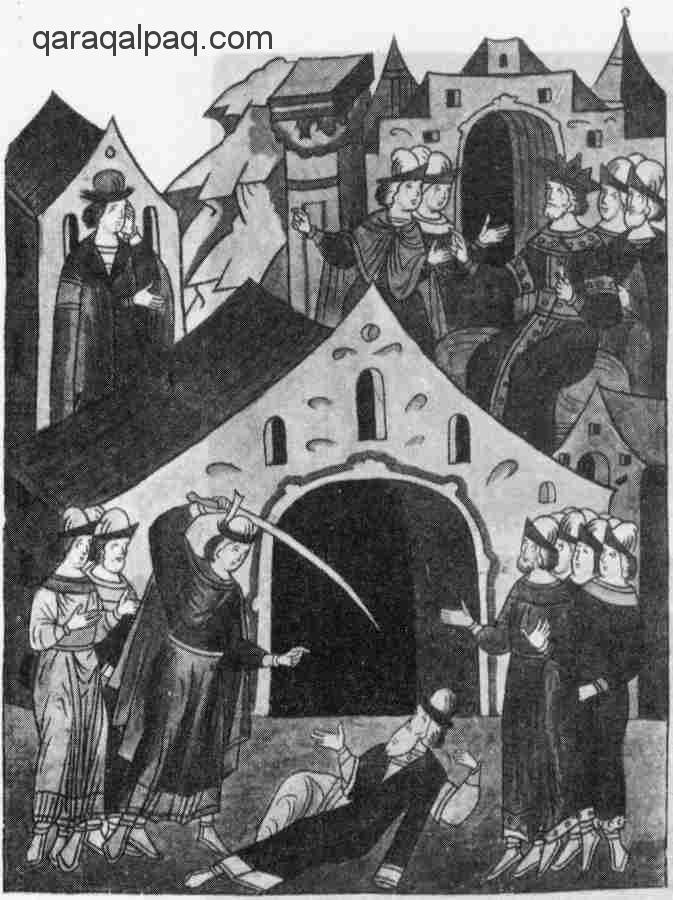

The battle of Liegnitz in Poland in April 1241. Today the town is known as Legnica.

The right wing under the command of Orda advanced from Vladimir with the objective of neutralizing Poland and Silesia before attacking Hungary from

the north. Their main objective was to prevent the army of Duke Henry of Silesia from meeting up with, and reinforcing, that of King Béla of

Hungary. They crossed the frozen Vistula to take Sandomir, Cracow and Wroclaw before defeating Duke Henry's Polish army at the battle of Liegnitz

in early April. They now rode south, planning to rendezvous with Batu close to Pest. The left wing meanwhile swept through the Carpathian Mountains,

overwhelming the Transylvanian army at Sibiu. The central army under Batu, Shiban and Sübetey headed directly towards Pest, breaking through

the heavily defended Verecke pass (the Gate of Russia) before taking the town of Vác. News that the Mongols had breached the pass reached

Pest on 15 March, causing panic. The Hungarian nobles accused the Cumans of being in league with the Mongols. Taking offence Khan Kotony rallied

his Cuman warriors and departed for Bulgaria, leaving the conventional Hungarian forces to defend the capital alone.

Detailed plan of the Mongol invasion of Hungary.

Batu was now phasing his advance so that he could join up with his right and left wings before engaging the main Hungarian army, in line with

Sübetey's main battle plan. However King Béla had led his forces out from Pest to intercept Batu before he could make his planned

rendezvous. The two opposing armies converged on the river Sajo and struck camp on different sides, the Hungarians choosing an exposed position on

the plain of Mohi. Avoiding a conventional battle, Sübetey launched a surprise attack on the Hungarians during the night of 10-11 April.

As his main forces crossed the bridge, catapults were used to clear defenders from the far bank. One division had already secretly crossed the river

to attack from the rear, so the Hungarians were surrounded and suffered devastating losses. The crafty Mongols had left a deliberate gap in their

encirclement to create a trap for the fleeing Hungarians, who were funnelled into marshland before being picked off by Mongol archers. Even so the

Mongols also suffered heavy losses.

According to the Tarikh-i Dost Sultan written by Ötemish Hajji in Khorezm in the 1550s, Batu's ulus was officially known as the White Horde of the Golden Threshold, Orda's the Blue Horde of the Silver Threshold and Shiban's the Grey Horde of the Steel Threshold. Unfortunately the terms White and Blue Horde have been much misused causing enormous confusion. In modern secondary sources their meanings are generally reversed, the term White Horde being applied to the ulus of Orda and Blue Horde to the ulus of Batu. To make matters worse, some authors refer to the ulus of Shiban as either the White Horde or the Blue Horde, while others define the White Horde as the combined uluses of Orda and Shiban. Even eminent scholars like Henry Hoyle Howorth were so confused that they assumed that Orda was higher ranking than Batu because the colour White ranked higher than Blue, when in fact Batu's ulus was the dominant half. Throughout this website we will comply with the original terminology, namely the White Horde of Batu and the Blue Horde of Orda. The Arabs and Persians commonly referred to Batu's ulus as the Khanate of Qipchaq, given that the overwhelming majority of his direct subjects were of Qipchaq origin and inhabited the Qipchaq steppes. The Masálak al-Absár written in the first half of the 14th century defined the territory of the Qipchaqs as extending in length from the Sea of Istanbul [the Marmaris] to the Irtysh River, and in breadth from Bulghar to the Iron Gate [Temür-Qahalqa or Derbent]. The Persians referred to the Qipchaq steppes as the Dasht-i Qipchaq. Western envoys like Carpini and Rubruck (see below) who visited Batu's encampment on the Volga only refer to the court of Batu or the "Land of Comania". In 1334 Ibn Battuta referred to the Dasht-i Qipchaq wilderness, six months journey in extent, three of which were in "the territories of Sultan Muhammad Uzbak". The Nikon and Novgorod Chronicles simply referred to Batu's ulus as the Orda or Horde. In western literature Jöchi's ulus is also frequently and mistakenly referred to as the Golden Horde, a name that was never used during its existence. The first use of this term dates from an account of a visit to Saray by the merchant F. A. Kotov in 1624, where he refers to the city, but not the Khanate, as the Zolotaia Orda. The same term is used again mainly in reference to the city some 15 times in the "History of the Kazan Khanate", dating from the second half of the 16th century or the early 17th century. Today the term Golden Horde usually refers to the combined uluses of Batu and Orda, although most of its history relates solely to the western part, there being far less source material concerning the eastern part.

A traditional map of the combined territories of the Golden Horde.

|

|

The qurultai finally took place at Köko Lake close to Qaraqorum in the spring of 1246, the guests being accommodated in 2,000 felt tents.

It was attended by Ordu, Shiban, Berke, Berkecher and Toqa-Temür from Jöch's ulus, Batu remaining on the Volga. It was universally

agreed that one of Ögedey's sons should inherit the throne, since Shiremün was still under age. Töregene Khatun favoured

Güyük, and as her other sons supported this proposal he was finally raised to the throne that August.

News of Batu's invasion of Eastern Europe had soon spread to the West, which had been engaged in its own intermittent Crusade against the Muslims in

the Holy Land. As early as 1238, Syrian envoys had visited England and France to suggest a Christian-Muslim alliance against the Mongol threat.

Appeals from Georgia and Galicia soon followed, emphasizing the extent of the threat. Yet some European rulers saw the Mongols as a potential ally

against the Muslims. The new Pope Innocent IV was so concerned about a further invasion that in 1245 he despatched four embassies to the Mongol Empire,

two led by Dominicans and two by Franciscans. Andrew of Longjumeau visited Syria and Palestine before later journeying to Mongolia with letters and

gifts from Louis IX of France. He arrived after the death of the Great Khan Güyük and had a rather fruitless encounter with his widow

Oghul-Qaimish (see below) who interpreted Louis's message as submission and sent a reply demanding gold and silver tribute. Ascelinus was sent via

Anatolia to Georgia where he visited the camp of Baichu, the Mongol general who had replaced Chormaghun in the Middle East in 1242. As for Lawrence

of Portugal's mission, it may never have got off the ground. It was the embassy of the 65-year-old Giovanni del Pian di Carpini to Central Asia and

Mongolia that has left us with the most memorable account. Carpini departed from Lyon in 1245 and, thanks to his breakneck ride across Central Asia,

we have been left with a detailed historical record of Güyük's election and subsequent enthronement.

|

Carpini turned out to be just one of some 400 envoys who had travelled from all quarters of the Mongol and non-Mongol world, ranging from Russia,

Georgia, Iran and Baghdad to Manchuria and China. The election was restricted to the Mongol inner circle and took place in a large white velvet

pavilion. The enthronement however was a more public event, staged in a brocade lined tent called the Golden Orda, and was accompanied by extravagant

gift giving and feasting. The Pope had sent two rambling messages to the stern Güyük Khan, the first asking him to convert to Christianity,

the second asking about his future plans, beseeching him to respect the lands of the Christians and warning him of the prospect of punishment in the

afterlife in the event of further Mongol atrocities. The Mongol Khan dictated his reply several months later, noting that the Mongols could not have

subjugated so vast a territory without the will of God. He warned the Pope that he would be regarded as an enemy if he failed to submit to Mongol

authority at Güyük's court at Qaraqorum.

|

On his way to Qaraqorum, Carpini had briefly visited Batu's encampment on the Volga. Batu was described as living "with considerable magnificence,

having door-keepers and all officials just like their Emperor". He occupied an elevated throne in one of several large and beautiful linen tents

captured from the King of Hungary. His encampment was on the eastern border of the territories of the Cumans who were divided between various tribal

chieftains. The Mordvins lived to the north of the Cumans and the Alans, Circassians and Kazars lived to the south. To the east was the waterless

country of the Qangli stretching as far as the lower Syr Darya. The minority of Qangli who had survived the Mongol invasion had been reduced to

slavery.

Some have interpreted Güyük Khan's response to Pope Innocent IV as a clear indication that he intended to mount a second and more comprehensive

invasion of the Christian West. Certainly one of his priorities seems to have been to oust Batu from the Khanate of Qipchaq. One of his first moves

was to despatch an army under Eljigitei to Iran with instructions to take control of Rum, Georgia and Aleppo "in order that no one else might

interfere with them and the rulers of those parts might be answerable to him for their tribute". The Mamluk writer Umari suggested that Eljigitei

was even authorized to arrest Batu's lieutenants in the Caucasus.

It seems that Güyük Khan was concerned about the increasing autonomy of the major ulus. According to Juvaini, Güyük

requested Batu to meet with him and Batu finally set out towards the east. Both Juvaini and Rashid al-Din agree that Güyük Khan also set

out with a large army on the pretext of returning to his yurt on the Emil River. Sorqoqtani Beki, the senior wife of Toluy, sent a warning

to Batu of Güyük's suspicious advance. Beki was a niece of the Kereit Ong Khan Toghrïl and a sister to one of Jöchi's widows.

However in April 1248 when Güyük Khan had only reached Qum-Sengir, one week's journey from the Uyghur capital of Besh-Baliq, he died, thus

averting a Mongol civil war. Batu received the news at Ala-Qamaq, not far from Lake Issyk Kul.

Chinggis Khan's chief sons were all dead so Batu was now the most senior of the elder princes. He was a forceful man, determined to prevent the

election of another Ögedeyid Khan. While the Great Khan's widow, Oghul-Qaimish, acted as temporary regent, Batu called the Mongol princes

together at Ala-Qamaq and persuaded them to support Toluy's eldest son Möngke, arguing that Ögedey's sons had ignored their father's

bequest to elect Shiremün while the late Toluy had originally been the rightful heir to Chinggis's throne. Rashid al-Din offers another version

with Batu calling the same meeting on the Qipchaq steppe, which the sons of Ögedey, Güyük and Chaghatay declined because it was not

in the traditional Mongol yurt. Sorqoqtani Beki instructed Möngke and his brothers to travel to Batu's court instead. Impressed with

Möngke's qualities, Batu then sent out messages to all the princes proposing that he should succeed Güyük.

Both authors agree that a qurultai was planned between the Onon and Kelüren Rivers but that it did not convene until the summer of 1251

because of delaying tactics by Ögedey's family. Batu remained on the Volga and was represented by his brothers Berke and Toqa-Temür

and his son Sartaq. Möngke was finally enthroned in the absence of the Ögedeyids. The Toluyids had gained control of the Empire. Apart

from the shrewd manipulation of Sorqoqtani Bek, we must remember that Möngke benefited from the fact that his family controlled the military might

of Mongolia. Shortly after the coronation a plot to oust the new Khan was uncovered. It led to a major purge and the execution of the rebel

Ögedeyid princes and their supporters, in addition to Güyük's widow Oghul-Qaimish, all the adult sons and grandsons of Chaghatay, and

Eljigidei and his family.

The forceful Batu had effectively staged a coup d'état, placing his friend and ally Möngke on the Mongol throne. With Möngke's

approval the Khanate of Qipchaq effectively gained autonomy, Batu reigning in the west and Möngke reigning in the east, the frontier between their

domains lying, according to Rubruck, between the Talas and Chu Rivers. As a bonus the Chaghatay ulus became divided, the eastern parts falling

under the control of Möngke, and Transoxiana and western Ferghana under the control of the Khanate of Qipchaq.

At the same qurultai in Mongolia Möngke reopened the Mongol offensives in the east and the west, assigning the campaigns to two of his

younger brothers. Qubilai was ordered to restart the campaign against the Sung in southern China, while Hulägu was to take control of Iran and

Iraq and to extend Mongol rule as far as Eqypt. Hulägu would first need to subjugate the Isma'ili imams in Mazandaran, the Assassins

who had attempted to assassinate the Great Khan in Qaraqorum, before destroying the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad and then moving on to Syria and Egypt.

His army included contingents provided by Batu and the other Mongol princes and included 1,000 households of Chinese catapult engineers.

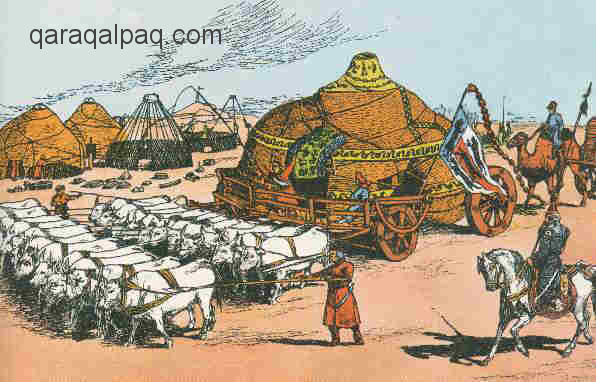

Thanks to the Franciscan evangelist William of Rubruck, we have a detailed picture of life in the domains of Batu and Möngke just two years after

this important event. Louis IX of France had received envoys from Eljigitei in Cyprus in 1248 while on his way to Palestine. They carried a friendly

letter and news of the Mongol plan to attack Baghdad. Carrying a letter from the King of France, Rubruck left Constantinople by sea for the Crimea

in May 1253 and then travelled in wagons across the Qipchaq steppes. The whole region was divided up between different tribal chieftains, each

"familiar with the limits of his pasturelands and where he ought to graze in summer and winter, and in spring and autumn". Each tribe roamed with

wagons loaded with their portable dwellings, accompanied by huge herds of cattle, sheep and horses. However beyond Kazaria the former Qipchaq

territories were now deserted. Rubruck crossed the Don and first reached the encampment of Batu's son, Sartaq, before being guided a further three

days to the Volga. Batu's yurt was on the eastern side of the lower Volga, while that of his brother Berke was further south on the route from the

Iron Gate (Derbent) in the Caucasus. Rubruck reached Batu's encampment in August 1253 and was shocked by its enormity:

"On sighting Batu's camp, I was struck with awe. His own dwellings had the appearance of a large city stretching far out lengthways and with inhabitants scattered around in every direction for a distance of 3 or 4 leagues [10-15 km!]. And just as everyone of the people of Israel knew on which side of the Tabernacle to pitch their tent, so these people know on what side of the residence to station themselves when they are unloading their dwellings. For this reason the court is called in their language orda, meaning "the middle", since it is always situated in the midst of his men, except that nobody takes up his station due south, this being the direction towards which the doors of the residence open. But to the right and left they spread themselves out as far as they like within the limitations imposed by the terrain, provided that they refrain from alighting directly in front of the residence or opposite it."Batu received them in a large pavilion, seated with his wife on a raised couch of gold, his face covered in red blotches. Rubruck subsequently accompanied the orda for five weeks as it made its way south down the Volga towards its winter quarters. Batu travelled with some 500 households in addition to his own. The encampment was so large that it was followed by a mobile bazaar. Rubruck then set off on the four month journey to the court of Möngke Khan in Mongolia, returning to Batu's camp in September 1254, carrying a letter from Möngke to Louis IX commanding him to submit as a vassal. By then Batu had established a new town called Saray (Persian for "palace") on the middle Aqtuba River, the eastern arm of the Volga, north of modern Astrakhan. The remains are located at the modern saltpetre mine of Selitrennoe-Gorodok, some 170km north of Astrakhan. Until then the only city on the Volga had been Bulghar, the former capital of the Bulghars, just south of the mouth of the Kama. Rubruck noted that Saray was on the east bank of the river and was the location of Batu's palace.

|

The first divide occurred with Hulägu who was slowly making progress in Iran and Iraq 'Ajami. The Isma'ilis (also known as the Assassins) had

surrendered to the Mongols at Alamut in late 1256 and some had fled to the Aral Sea delta in the region of present-day Moynaq. By the start of 1258

Hulägu's army were preparing to surround Baghdad. By late February the city had been overwhelmed, the defenders massacred and the Caliph trampled

to death by horses. Now Hulägu directed his army northwards, taking Azerbaijan before attacking Muslim Syria in September 1259. By February

1260 Damascus had been overthrown. In Egypt the Mamluks readied a large army for the threatened Mongol invasion. However the arrival of news of the

Great Khan Möngke's death in China in 1259 left Hulägu in an exposed position and he withdrew the bulk of his forces back to Iran, leaving a

much reduced force in Syria under Kit-Buqa. In a letter to Louis IX Hulägu indicated the cause to be a shortage of fodder. Kit-Buqa met Qutuz

and his Mamluk army at Ayn Jalut in Galilee and the Mongols were defeated and driven from Syria which became Mamluk. Qutuz was rewarded for his

victory with a putsch that placed Sultan Baybars, one of his commanders, on the throne.

For Berke, Hulägu's advance into the pasturelands of Azerbaijan was an encroachment upon the territories of the "House of Jöchi", which had

already been trodden upon by the "hoof of the Tatar horse", thereby breaking Chinggis Khan's yasa. Although the Caucasus Mountains formed a natural

boundary between the Iranian and Qipchaq domains, the Qipchaqs had traditionally pastured on the steppes of Arran and Azerbaijan. We also understand

from the Mamluk writer al-Umari that Möngke had previously assigned the northern Iranian cities of Tabriz and Maragheh to Berke's ulus.

While Islamic authors have played on Berke's indignation over the murder of the Caliph, the primary reason for the dispute was the challenge to the

status and sphere of influence of the Qipchaq Khanate. Berke also knew that the stability provided by Hulägu's new Ilkhan state would open up a

competitive trade route between the Mongol east and the west, which at that time was channelled mainly via Khorezm and the Volga.

Berke had originally supplied a contingent of troops to Hulägu's army. It is possible that he subsequently ordered their recall because

Hulägu commenced a massacre of the Jöchid forces. At least three Jöchid princes who had participated in the siege of Baghdad were

killed at Hulägu's camp, one for sorcery and two supposedly by poison. The surviving Jöchid forces fled, some making their way back to

Qipchaq, a small number managing to reach Cairo. Berke responded by sending an army, led by his nephew Prince Noghay (a great grandson of Chinggis),

through the Caucasus Mountains into Azerbaijan. Hulägu moved north and defeated Noghay in November 1262, forcing him back through the Derbent

pass back onto the Qipchaq steppe. The Ilkhanids then crossed the Terek River, capturing an empty enemy encampment, only to be routed in a surprise

attack by Noghay's forces. Many of them were drowned as the ice broke on the frozen Terek River. It was the first encounter between two opposing

Mongol armies.

The outbreak of war between Berke and Hulägu had occurred while Niccolo and Maffio Polo were at Saray, having arrived one year earlier by means

of Sudaq with jewellery from Constantinople to trade with the Khan . Barred from returning to the Mediterranean through Persia, they decided to

travel eastwards to Bukhara, first crossing the Volga at Ukek.

Sultan Baybars saw the Khanate of Qipchaq as a natural ally against the Ilkhanate of Persia and ambassadors were exchanged, communication being

facilitated by the Greek recapture of Constantinople under Michael Palaeologus in 1261. The Mamluks were ethnically Qipchaq and obtained many of their

soldiers in the form of slaves from the Qipchaq steppes. While Berke and Baybars considered several options, no joint campaign was ever agreed

although the increasing power of the Mamluks kept Egypt and Syria away from Ilkhanid control.

Meanwhile the death of the Great Khan Möngke had led to a contest between two of his brothers, Qubilai and the younger Ariq-böke.

Ariq-böke, who was responsible for the homeland and was already in Qaraqorum, may have been Möngke's chosen successor. He therefore became

the temporary regent and began the preparations for a qurultai. Qubilai meanwhile brought his army north to his summer encampment on the

edge of the Gobi Desert, close to modern Duolun and, at a stage-managed qurultai, he declared himself Supreme Khan. This was a clear breach

of Chinggisid tradition and the advisors at Möngke's court encouraged Ariq-böke to also take the throne. Berke now threw his support behind

Ariq-böke, while Hulägu supported Qubilai, splitting the Mongol ulus down the middle.

A four-year-long civil war ensued in which Qubilai's military forces eventually proved decisive. Qubilai won the first battle in Kansu and then

advanced into Mongolia, forcing Ariq-böke into the Upper Yenisei. Ariq-böke then recaptured Qaraqorum and engaged Qubilai close to the

Gobi desert. At this point the civil war appeared evenly balanced.

Ariq-böke had earlier placed Chaghatay's grandson Alughu in charge of the former Chaghatay ulus of East Turkestan with the task of

preventing reinforcements being sent from Hulägu to Qubilai. Alughu exploited the opportunity to rebuild his ulus and took control of

Samarkand and Bukhara, before reneging on Ariq-böke and declaring his support for Qubilai. His defection turned the tide, allowing Qubilai to

attack from the east to re-occupy Qaraqorum, while Alughu attacked from the west. Ariq-böke was trapped and forced to surrender in 1264. Alughu

then declared war on Berke Khan, seizing Otrar and Khorezm. While left bank Khorezm would eventually be retaken, the Qipchaq Khanate had lost its

control over Transoxiana.

In the year of his victory, 1264, Qubilai decided to build a new capital of the empire at Khanbaliq, the City of the Khan, known in the west as

Cambalec and better known today as Beijing. Qubilai's victory and his removal of the throne from Qaraqorum further isolated the Khanate of Qipchaq

from the other Mongol ulus, increasing its autonomy. Hulägu on the other hand styled himself the Il-Khan, or subservient Khan,

indicating his subordination to the new Great Khan in the East.

Hulägu's death in 1266 may have given Berke another opportunity to take control of the Caucasus. In the following year he advanced into

Azerbaijan with his general Noghay, but was repulsed by Hulägu's son Abaqa. Berke was killed at a battle at Tiflis in Georgia and Noghay lost

an eye.

Berke was succeeded by Batu's grandson Möngke Temür, who was a non-Muslim. Möngke Temür maintained the alliance with Mamluk

Egypt and Byzantium and seems to have reached a stalemate with the new Il-Khan Abaqa. However he continued to oppose the rule of the usurper

Qubilai Khan and supported the Ögedeyid prince Qaidu's fight against Baraq Khan, the ally of Qubilai, who was now in control of Chaghatay's

ulus. To emphasize the Khanate of Qipchaq's independence from Qubilai, Möngke Temür began to issue his own coinage, which bore

no reference to the Great Khan.

Mongol trade with Byzantium and the Mediterranean was increasing with goods passing from Saray to Tana to be exported through the Khanate of Qipchaq

port of Sudaq in the Crimea. The Genoese had acquired a monopoly on the trading rights across the Black Sea from Michael Palaeologos, who had

dislodged the Venetians from Constantinople. Now Möngke Temür granted the Genoese permission to establish a port at Caffa. Berke had been

responsible for transforming Saray from a camping ground to a town or city, probably founding a mosque or medresseh and even a bishopric. Indeed the

anonymous Arab writer of the Mesalek al-Absar even claimed that Berke was the founder of Saray: "The town stood in a salty plain, and was

without walls, though the palace had walls flanked by towers". Apparently the town was large and had markets, medressehs and baths. It became known

as Berke Sari, while the Dasht-i Qipchaq became known as Berke's steppe.

When Möngke Temür died in 1280 he left the Khanate in an economically and militarily powerful position. It still remained primarily a

nomadic state whose population was overwhelmingly Turkic, the number of Mongols having progressively declined as a result of the continuing demands

upon the Qipchaq Khanate for military resources. Now the Mongol leadership was increasingly coming under the cultural, linguistic, and religious

influence of its mainly Muslim Turkish population. Its only sedentary centres were located in Saray, the Crimea and in Urgench, but these were all

rapidly growing and were the main centres of Muslim teaching. Of course the bulk of the Qipchaq nomads still remained pagan at this time.

The Mongol Empire itself had been permanently fractured into four effectively independent khanates: Qubilai in China, where the Yüan dynasty

had been established in 1271; the Chaghatay Khanate in Transoxiana and Ferghana; the Il-Khante in Iran and Iraq; and finally the Khanate of Qipchaq.

These divisions would lead to a halt in the empire's outward expansion as its military resources became increasing redirected towards internal conflicts.

Emir Noghay and Toqta Khan

Emir Noqai or Noghay, the grandson of Berke's younger brother Bo'al, emerged as an increasingly powerful general during the reign of Berke and

Möngke Temür. However he lacked the military talents of Batu or his great-grandfather Jöchi. He had led an unsuccessful raid on

Hungary in 1261, and commanded two failed campaigns against Hulägu - in 1262 and 1267. In the latter debacle he not only lost an eye but

witnessed the death of his sovereign. However he was successful against the Byzantine Empire in 1265 after it had invaded Bulgaria, forcing it into

an alliance, the Emperor Michael Palaeologos offering the hand of one of his illegitimate daughters to Emir Noghay. In 1271 he invaded Bulgaria at

the request of his father-in-law who was seeking revenge against the King of Bulgaria for a raid against Thrace. Like Berke, Noghay was a Muslim,

having been converted at some time prior to 1262. Noghay produced three legitimate sons: Cheke, Teke and Buri.

Noghay does not appear to have inherited his own ulus, and was always described as a commander, suggesting that he may not have been a

legitimate son. Instead he seems to have carved out his own fiefdom in the western part of the Qipchaq Khanate. Grousset refers to a Franciscan

envoy to the Crimea named Ladislas, who noted that while the Khans of Qipchaq (Töda-Möngke and Töle-Buqa, see below) occupied the

region around Saray, Noghay roamed further west in the region of the Don and the Donets. From the 1260s onwards he controlled the westernmost region

of the Khanate of Qipchaq, effectively establishing an independent province on the western and northern shores of the Black Sea, ranging from the

lower Danube to the lower Don and extending north to the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains (in other words a large part of present-day Moldova

and the Ukraine). His influence extended into the Balkans and northern Bulgaria. His main encampment was on the River Bug, which enters the Black

Sea just west of the Crimea.

After the death of Möngke Temür the Khanate of Qipchaq entered a difficult period with a succession of leaders consumed by infighting and

intrigue as the various tribal factions vied for power and control of the valuable trade route. Noghay exploited these weaknesses by building up his

own following and extending his control over the running of the Khanate until his death in 1300. Unfortunately this internal division also provided

opportunities for the Khanate's rivals and vassal states.

The Qipchaq throne now passed to Möngke Temür's far less competent younger brother, Töda-Möngke. In 1281 the new Khan summoned

the Russian princes to Saray to renew their patents, but Dmitry Aleksandrovitch of Vladimir refused to pay homage. Töda-Möngke transferred

the Princedom to Dmitry's younger brother Andrei who, with Tatar support, invaded the Principality of Vladimir forcing Dmitry to flee. Dmitry now

sought assistance from Noghay who issued his own patent in return for Dmitry's submission and promise of future tribute. Noghay then sent troops to

Vladimir to oust Andrei from power.

After becoming a devout Sufi Muslim in 1283, the ineffectual Töda-Möngke was declared insane and deposed by his nephews Töle-Buqa and

Könchek (grandsons of Batu's second son Toqoqan) along with two of Möngke Temür's sons. According to Rashid al-Din the two brothers

ruled the Khanate jointly.

That same year Noghay briefly supported his father-in-law in Thessaly and in 1284 staged a raid on Bulgaria, Serbia, Macedonia and Thrace, forcing the

submission of the Bulgarian ruler George Terter and the Serbian king Stefan Uros II Milutin. When Terter fled to Byzantium, Noghay placed his own

vassal Smiltzos on the throne. In the winter of 1285-86 Noghay waged a joint campaign with Töle-Buqa against Hungary, which was under the rule

of Ladislas IV, known as the Cuman because of his Qipchaq mother. The venture was a disaster with atrocious weather causing the Qipchaq army to suffer

heavy losses during their advance on the Danube and also on their retreat. A quarrel arose between Noghay and Töle-Buqa with many discontented

warriors, including Toqta and several of Möngke Temür's other sons, finding refuge in Noghay's encampment.

In 1287 Noghay and Töle-Buqa set out on another unsuccessful raid, this time on Poland. Ladislas visited the Crimea in the very same year and

discovered that Noghay was perceived to have equal rank with Töle-Buqa.

It was Töle-Buqa's insistence on trying to recover the pasturelands of Azerbaijan from the Ilkhans that led to his downfall. His first attempt

in 1288 was a failure, as was his second attempt in 1290. With his reputation shattered he was challenged by Toqta, Möngke Temür's

capable son. Töle-Buqa attempted to have Toqta arrested but he escaped to find sanctuary at Noghay's encampment. In 1291 the ruthless Noghay

hatched a plot to capture Töle-Buqa, handing him over to Toqta to be assassinated, thereby making way for Toqta to be installed on the throne

as Noghay's puppet.

However Toqta had a mind of his own and he would eventually restore peace and order to the Khanate. His period of governance, coupled with that of

his nephew Özbeg, would go down as the Golden Age of the Khanate of Qipchaq.

Toqta's first challenge came from three Russian princes – Dmitry Aleksandrovitch of Vladimir, Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver and Daniel Aleksandrovich

of Moscow – who refused to pay homage to him in Saray, having allied themselves to Noghay. Exploiting the situation, Andrei and the Rostov princes

submitted themselves to Toqta instead, raising their complaints about Dmitry's loyalty. Noghay refused to obey Toqta's summons to Saray. In 1293

Toqta staged his first campaign against Noghay, also sending forces to Vladimir to oust Dmitry and install Andrei. Dmitry fled and died the following

year, permitting Andrei to rule as the legitimate prince.

The final showdown between Toqta and Noghay is described in different ways by different sources - Marco Polo picked up part of the story while

imprisoned in Genoa in 1299; Rashid al-Din's account dates from 1307, while the Arab author Al-Nuwayri produced his enormous encyclopaedia in 1331.

The underlying cause of the dispute was fairly fundamental – by 1296 Noghay had effectively established his own independent Khanate. That year his

mint, first established in the fortress of Saqchi in 1286, ceased issuing coins in the name of Toqta in favour of those bearing Noghay's own name

and tamga, and some with the name of his son Cheke. Noghay had also assisted the Venetians to break the Genoese monopoly on Black Sea trade, causing

the Genoese to complain loudly to Toqta at his court in Saray. However it is also possible that something more mundane sparked the final confrontation.

Marco Polo suggests two of Töda-Möngke’s sons approached Toqta seeking vengeance for the death of their father, while Rashid al-Din suggests

there had been problems following the marriage of Noghay's daughter to Toqta's brother-in-law. Al-Nuwayri on the other hand suggests that Noghay was

providing sanctuary to several tribal chieftains and refused to hand them over to Toqta. Whatever the cause, it seems that Noghay was threatened by

Toqta and rose to the challenge.

According to Rashid al-Din, Toqta first attempted to advance on Noghay but was frustrated by his inability to cross the Dnieper for lack of ice. One

year later Noghay headed for the Don on the pretext of peacefully resolving his differences with Toqta at a qurultai, while actually hoping

to catch the Khan before he had time to rally his forces. Toqta hastily gathered his army and engaged Noghay in battle at Bakhtiyar on the east bank

of the Don, but was heavily defeated and forced to retreat to Saray. While the location of the battle may be uncertain, with Marco Polo mentioning the

Plain of Nerghi and Al-Nuwayri the alternative site of Yacssi, it must have taken place in the winter of 1296-97 since news of Toqta's major defeat

reached Makrizi in Cairo in February-March 1298.

Noghay now sent his grandson to the wealthy Genoese ports of Sudaq and Caffa in the Crimea to collect tribute. After the grandson was assassinated,

Noghay led a punitive expedition against the Genoese, taking booty and many prisoners. The Genoese then sought a settlement, which required the return

of the captured prisoners. However this caused splits to emerge in Noghay's camp, with some princes proposing to side with Toqta in return for an

amnesty, offering to raise Teke as their Khan if only he would join them. When Teke went to negotiate with the dissidents he was captured, forcing

Cheke to purge the radicals and decapitate one of their leaders. The incident left a feeling of distrust between the two brothers and when Cheke made

a failed attempt to have Teke killed it caused a revolt among some of his military leaders.

When news of these divisions reached Toqta he gathered his reinforcements and crossed the Dnieper with a huge army approaching Noghay's encampment

on the River Bug. While Noghay attempted to parley, his son Cheke attempted to outflank the enemy. Informed of the intrigue, Toqta ordered his troops

to engage with Noghay's supporters. The battle of Kügenlik resulted in many casualties and Noghay's forces were trounced. Noghay was finally

beheaded by a Rus soldier while his sons retreated to the country of the Keler and the Bashkirs (Hungary). Al-Nuwayri dates this final battle to 1299.

|

This defeat had profound consequences for Noghay's sons and supporters. Cheke immediately laid claim to his fathers domains but was forced to seek

refuge with the As or Alans to avoid being captured by his pursuers. Cheke had earlier married one of George Terter's daughters and decided to head

for Bulgaria with his supporters, where he joined forces with his brother-in-law Svetoslav. Marching into Tarnavo in late 1299 Cheke ousted the

temporary ruler Ivan II and placed himself on the Emperor's throne with Svetosalv installed his deputy. It was here that he was approached by his

mother and brother Teke, who proposed that he make a peace deal with Toqta, an idea that so outraged him that he had them both murdered, creating a

further schism through the ranks of Noghay's ruling tribe. Fearing reprisals from Toqta, Svetoslav finally deposed Cheke in 1300 and had him strangled

in prison. After receiving Cheke's head, Toqta installed Svetoslav as the new Emperor.

Noghay's former appanage had been divided among Toqta's family, the largest part going to his brother Serai Bugha. Although two of Noghay's

sons were dead, Buri was still seeking revenge for the death of his brothers and father. In 1301 Buri persuaded Serai Bugha to rebel against Toqta,

but the plot was uncovered and Buri and Serai Bugha were both killed, Serai Bugha's territories now passing to one of Toqta's sons. According to

al-Nuwayri one of Cheke's sons, Kara Kesek, had survived the killings and fled with two of his relatives and about 3,000 supporters to "the country

of Shishmen", reaching a place called Bdin, which Vásáry interprets as Vidin, a semi-independent Bulgarian state on the southern bank of

the Danube. The Tatars formed a military alliance with Shishmen and settled in his territory.

Although Toqta was finally free from Noghay interference, the tribal leadership of his White Horde had been shaken by the internal conflict and its

vassal states had gained confidence. Toqta now weakened the White Horde economy by picking a fight with the Genoese colonies in the Crimea. Concerned

by the continuing export of Qipchaq slaves for the Mamluk army, Toqta arrested the Genoese residents of Saray in 1307 and then besieged the port of

Caffa. The Genoese responded in May 1308 by departing by sea leaving their city in flames. They then established a naval blockade of the Black Sea

ports, depriving the Horde of valuable revenues.

Despite the ongoing struggle among the ruling families for power, life within the Khanate of Qipchaq remained orderly. Thanks to the so-called

Pax Mongolica, travel remained safe and commerce was buoyant. Ambassadors began to flock to Saray, Qaraqorum and Beijing from all quarters of

Eurasia. In return two Mongol ambassadors even turned up in Northampton in 1307 carrying letters for Edward II.

In his final years Toqta turned his attention back to Russia and considered eliminating the special status of the Grand Duchy of Vladimir, placing

all the Russian princes on the same level. In 1312 he set off by boat up the Volga to see these territories at first hand but in August he fell ill

and died before leaving the boat.

Özbeg Khan

Under the rules of accession the 30-year-old Özbeg, eldest son of Toqta's older brother Togrül, was first in line for the Qipchaq throne.

In the earlier conflict between Töle-Buqa and Toqta, Togrül had supported the incumbent Khan and had consequently been eliminated by his

ambitious younger brother. The latter clearly desired that Tukel (sometimes called Elbasmu), the eldest of his three surviving sons, would succeed

him and as a result had sent the young Özbeg into exile with the Circassians. It seems that the ulus beys were divided over the issue.

According to Rashid ad-Din some leaders of the Mongol ruling tribes did not favour Özbeg because of his Islamic leanings and planned to

assassinate him at a feast before announcing their decision to install Tukel. However Toqta's former advisor, Qutlugh Timur, who seems to have

been the chief of the ulus beys, supported Özbeg and warned him of the plot. Together Qutlugh Timur, Özbeg and Togrül's

widow Bayalun conspired against Tukel and his emir, Özbeg killing the former at Serai and Qutlugh Timur killing the latter. Once enthroned

in early 1313, Özbeg conducted a major purge of the disloyal tribal leaders and shamen. Almost one hundred princes and tribal aristocrats were

massacred.

The imman Badr al-Din al-Ayni recorded that Qutlugh Timur secured Özbeg's prior agreement to adopt Islam before supporting him to

become Khan, suggesting that there may have been political reasons behind his conversion. The Mongol rules of inheritance meant that the ulus

of every emir was divided among his sons following his death. The Khanate was becoming more and more fragmented into an increasing number

of smaller fiefdoms, creating the potential for greater internal conflict. It is possible that Islam was seen as a potential unifying force,

especially since many important groups within the Khanate were already believers, from the important Bulghar merchants on the Volga, to the Khorezmian

Sarts and some of the senior Qipchaq military, as were its Mamluk allies and southern Ilkhanate neighbours. According to the anonymous 15th to

16th century Shajarat al-atrak, Özbeg Khan was converted by the Sufi shaykh Sayyid Ata of the Sunni order of Kwaja Ahmed Yassawi

of Yasi (modern Turkestan), who renamed him Ghiyath ad-Din Muhammad Özbeg. Sayyid Ata had been sent as a missionary from Tashkent to spread

Islam in the Qipchaq steppes. Apparently those who subsequently converted and accompanied Sayyid Ata back to Turkestan adopted the name of their

recently converted Khan, Özbeg. Of course it is likely that this was no more than a retrospective attempt to provide an explanation of the

origin for the ethnonym Özbeg (Uzbek).

Özbeg was to rule for almost 30 years, re-establishing centralized rule from Saray and restoring stability. Qutlugh Timur remained one of

Özbeg's closest advisors but was mysteriously assigned the governorship of Khorezm in 1321 in place of Bayalun's brother Bay Timür. Two

years later he was reinstated as Özbeg's deputy.

Özbeg maintained the alliance between the Khanate of Qipchaq and Byzantium as well as with the Egyptian Mamluks. One of his sons was married

to a daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Andronik Paleologus. In 1316 the Mamluk Caliph Nassir sent envoys to Saray requesting a marriage alliance with

a Chinggisid princess, a proposal that initially came as a shock to Özbeg's court. It was not until 1319 that Princess Tulunbeg departed for

a grand welcome in Cairo, although it seems that the marriage was short-lived, causing consternation in Saray. However after the Mamluks concluded

a peace treaty with the Il Khanate in 1323, the influence of the Khanate of Qipchaq in Egypt began to wane. The establishment of the Ottomans in

Constantinople in 1354 would lead to the final termination of commercial relations between the Nile and the Volga.

Under Özbeg the Khanate of Qipchaq maintained its hostile stance against Iran. The situation was not helped by Baba Bahadur, a Chinggisid

prince who relocated his tribal followers to Khurasan in 1305. In 1315 he invaded and pillaged Khorezm, only being ousted as a result of the

intervention of friendly Chaghatay forces based in Khojent. A furious Özbeg sent an ambassador to Iran to complain about the incursion,

threatening military action unless the perpetrator was brought to justice. The Il-Khan Öljeytü chose a diplomatic solution and had Baba

and his son executed.

After Öljeytü's death (in 1316) and the enthronement of his 13-year-old son Abu Said, Özbeg launched an attack against the Il Khanate,

marching south through Derbent in 1318-19. Following the news of Özbeg's invasion, many of Abu Said's forces deserted him, but he was saved by

the arrival of his military leader, Emir Choban. In 1325 Özbeg led a second expedition into Iran, which was again repulsed by Choban back onto

the Qipchaq steppes. Another major campaign was launched against Azerbaijan in 1334-35. In 1335 Abu Said was in the process of launching a

counter attack against the Qipchaq Khanate when he was killed, possibly by poison. He left no male heirs, ending the line of Hulägu and

initiating a feud for the succession. In their desperation to find a leader the Il Khanate ulus beys even approached Özbeg, but he

declined after consulting with his senior emir, Qutlugh Timur. It was the start of the Il Khanate's fragmentation and decline into chaos.

In Russia, the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir had passed to Mikhail of Tver in 1304, but he encountered difficulties with the important commercial

centre of Novgorod, which refused to accept his choice of governors. Although Novgorod acknowledged his position in 1307, it continued to resist

the collection of tribute. Finally Mikhail withdrew his governors in 1312 and laid siege to the city. Following Özbeg's succession the

following year, Mikhail paid homage to the new Khan, only to find that his absence had been exploited by Yuri, Prince of Moscow, offering to take

the Novgorod throne. Mikhail appealed to Özbeg for military assistance and by 1316 had regained control of Novgorod. In the meantime, Yuri

had been summoned to the Volga by the Khan, where he managed to convince Özbeg that he could harvest a higher level of tribute from the Rus

territories than his rival Mikhail. Özbeg granted patents to Yuri and cemented them by offering one of his sisters in marriage. However after

Yuri returned to Moscow he was attacked by Mikhail. Özbeg's sister was captured and eventually died. It was now Yuri's turn to appeal to

Özbeg. Mikhail was summoned to Özbeg's encampment close to Derbent in 1319, where he was assassinated.

|

In 1321 Yuri collected taxes from Dmitri of Tver, the son of the late Mikhail, but instead of delivering it to Saray, kept it for himself. Now Dmitri

grabbed the initiative and travelled to Özbeg's court, revealing Yuri's treachery and convincing Özbeg to endow him with his father's

patent. Yuri responded by assembling a delegation in Novgorod to travel to the Volga with his treasury, only to be robbed along the way by Dmitri's

brother. It took several years for Yuri to accumulate enough wealth to feel confident enough to restart his journey, only to be assassinated by

Dmitri after entering the Khanate of Qipchaq.

|

When Mongol tax assessors (one of whom was Özbeg's cousin) entered Tver in 1327, they were killed by its inhabitants, responding to a wild

rumour that they were about to be forcibly converted to Islam. Ivan Daniilovich of Moscow, Yuri's brother, immediately sent his own governors to

Novgorod while setting off himself to Özbeg's encampment. He returned at the head of a Mongol army in order to punish Tver for its uprising

and rewarded the Mongol generals and emissaries with a special tribute. In turn Özbeg rewarded Ivan I with the Grand Principality of Vladimir,

Novgorod and Moscow. He chose Moscow as his residence and enclosed it with a rampart. He and his successors ruthlessly exploited their reluctant

subjects on behalf of the Khanate for the next forty years, gradually building up their power base in northern Russia.

The Khanate of Qipchaq in the 1330s

Many historians claim that the heyday of the Khanate of Qipchaq occurred during the reign of Özbeg Khan. While this was certainly not the case

in military terms, it probably was so economically. Of course Özbeg Khan maintained Mongol nomadic traditions, constantly moving his

orda, or city on wheels, across the steppes to the north of the Caucasus Mountains and between the Caspian and Azov Seas. Yet he had also

established a strong administration at Saray led by a chancellor or vasir with the power to manage the Khanate in the absence of the Khan

and resolve issues without consulting the ulus emirs. It seems that, from around the turn of the century, Qipchaq had replaced Mongol as the

language of the administration, while during Özbeg's reign Islam gained an increasing hold of the Mongol and Qipchaq aristocracy and

administration. The encouragement and development of trade remained a high priority and relations with the Genoese and Venetians remained strong,

the latter being allowed to build a colony at Tana, at the mouth of the Don, in 1332. Özbeg's administration unified the monetary and weight

systems and introduced a single currency called pools, which was minted in Bulghar, Mukha and Urgench.

According to the 14th century scholar al-Umari, the Khanate of Qipchaq consisted of four parts, the Dasht-i Qipchaq, Saray, the Crimea and

Khorezm. In fact it consisted of five parts if one considers the northern Bulghar territories, or six if one includes the vassal Principalities of

Russia. Its main cities and towns were located in the following regions:

Ports on the Volga and Don:

|

From Özbeg's encampment Ibn Battuta claims to have travelled 10 days to the city of Bulghar, but left us no description of that city. Perhaps

this is not surprising since the journey would have taken him far longer. He says that he had intended to travel further north to the "Land of

Darkness", a further 40 days on from Bulghar, but was dissuaded by the high cost of hiring dog sleighs. From Bish Dagh he accompanied the ordu

as it travelled to Hajji Tarkhan, where the Khan spent the hardest months of the winter. Hajji Tarkhan was "one of the finest cities, with great

bazaars, built on the river Itil [Volga], which is one of the great rivers of the world". As the surface of the river turned to ice it was

covered with straw and used as a highway for wagons.

One of the Khan's wives, the Khatun Bayalun, was a daughter of the Greek King of Constantinople and had been given permission to visit her father from

Hajji Tarkhan. Ibn Battuta grasped the opportunity to accompany her retinue on the journey to this great city. Surprisingly they travelled overland,

crossing the Volga at Ukek, "a city of middling size, with fine buildings and abundant commodities, and extremely cold". From there they journeyed

to Baba Saltuq, possibly located on the lower Dnieper or in the Dobruja region of Romania, passing through an uninhabited waste before reaching the

territories of the Greeks.

On his return he found the Khan had moved on to Old Saray and he travelled on a 3 day journey up the frozen Volga to meet him. He discovered that

the capital was a thriving multi-cultural city:

"The city of al-Sara is one of the finest of cities, of boundless size, situated in a plain, choked with the throng of its inhabitants, and possessing good bazaars and broad streets. We rode out one day with one of its principal men, intending to make a circuit of the city and find out its extent. Our lodging place was at one end of it and we set out from it in the early morning, and it was after midday when we reached the other end. There are various groups of people among its inhabitants; these include the Mughals [Mongols], who are the dwellers in this country and its sultans, and some of whom are Muslims, then the As [Alans], who are Muslims, the Qifjaq, the Jarkas [Circassians], the Rus and the Rum – all these are Christians. Each group lives in a separate quarter with its bazaars. Merchants and strangers from the two Iraqs, Egypt, Syria and elsewhere, live in a quarter which is surrounded by a wall for the protection of the properties of the merchants. The sultan's palace is called Altun Tash, altun meaning gold and tash head [actually stone]."Ibn Battuta travelled from Saray to Urgench via Saraichik, spending 30 days to cross the Ustyurt desert:

"... we arrived at Khorezm [Urgench] which is the largest, greatest, most beautiful and most important city of the Turks. It has fine bazaars and broad streets, a great number of buildings and abundance of commodities; it shakes under the weight of its population, by reason of their multitude, and is agitated by them in a manner resembling the waves of the sea. I rode out one day on horseback and went into the bazaar, but when I got halfway through it and reached the densest pressure of the crowd at a point called al-Shawr [crossroad], I could not advance any further because of the multitude of the press, and when I tried to go back I was unable to do that either, because of the crowd of people. So I remained as I was, in perplexity, and only with great exertions did I manage to return."The city had a new college (medresseh), recently built by Qutlugh Timur in which Ibn Battuta stayed, a cathedral mosque built by the emir's pious wife, the Khatun Tura beg, a hospital with a Syrian doctor, and a nearby hospice built over the tomb of Najim al-din al-Kubra.

|

This page was first published on 12 October 2008. It was last updated on 3 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2018. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |